9 Tales of Terror from the Ancient World

From Vergil to Heliodorus, there's a fright for everyone.

A werewolf by Lucas Cranach the Elder (image from Wikimedia Commons)

A werewolf by Lucas Cranach the Elder (image from Wikimedia Commons)Every Classicist knows that ancient literature is replete with delightfully ghoulish tales of terror. Ghosts parade through epic, monsters prowl through myth, and ghastly murders are fairly standard in a good tragedy. The stories collected here run the gamut of horror — from dead to undead to everything in-between — and demonstrate some of the nightmarish happenings one can expect from ancient literature.

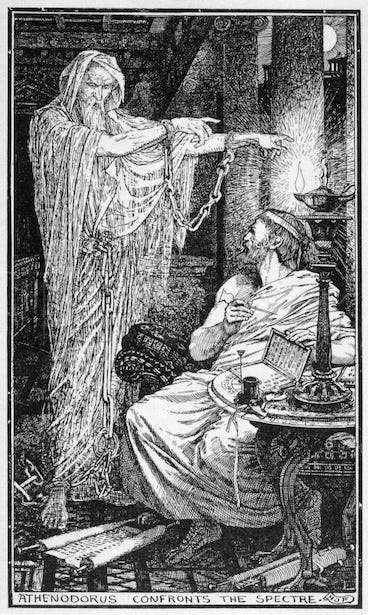

1. A Haunted House in Athens

Pliny the Younger writes of the philosopher Athenodorus’s experience with a cursed house, complete with rattling chains and mouldering bones (Letters, VII, 27, 5–11; Latin from The Perseus Digital Library, English from Attalus).

Erat Athenis spatiosa et capax domus sed infamis et pestilens. Per silentium noctis sonus ferri, et si attenderes acrius, strepitus vinculorum longius primo, deinde e proximo reddebatur: mox apparebat idolon, senex macie et squalore confectus, promissa barba horrenti capillo; cruribus compedes, manibus catenas gerebat quatiebatque. Inde inhabitantibus tristes diraeque noctes per metum vigilabantur; vigiliam morbus et crescente formidine mors sequebatur. Nam interdiu quoque, quamquam abscesserat imago, memoria imaginis oculis inerrabat, longiorque causis timoris timor erat. Deserta inde et damnata solitudine domus totaque illi monstro relicta; proscribebatur tamen, seu quis emere seu quis conducere ignarus tanti mali vellet […] Ibat illa lento gradu quasi gravis vinculis. Postquam deflexit in aream domus, repente dilapsa deserit comitem. Desertus herbas et folia concerpta signum loco ponit. Postero die adit magistratus, monet ut illum locum effodi iubeant. Inveniuntur ossa inserta catenis et implicita, quae corpus aevo terraque putrefactum nuda et exesa reliquerat vinculis; collecta publice sepeliuntur. Domus postea rite conditis manibus caruit.

There stood in Athens a spacious and roomy house, but it had an evil reputation of being fatal to those who lived in it. In the silence of the night the clank of iron and, if you listened with closer attention, the rattle of chains were heard, the sound coming first from a distance and afterwards quite close at hand. Then appeared the ghostly form of an old man, emaciated, filthy, decrepit, with a flowing beard and hair on end, with fetters round his legs and chains on his hands, which he kept shaking. The terrified inmates passed sleepless nights of fearful terror, and following upon their sleeplessness came disease and then death as their fears increased. For every now and again, though the ghost had vanished, memory conjured up the vision before their eyes, and their fright remained longer than the apparition which had caused it. Then the house was deserted and condemned to stand empty, and was wholly abandoned to the spectre, while the authorities forbade that it should be sold or let to anyone wishing to take it, not knowing under what a curse it lay […] The spectre walked with slow steps, as though burdened by the chains, then it turned off into the courtyard of the house and suddenly vanished, leaving its companion alone, who thereupon plucked some grass and foliage to mark the place. On the following day he went to the magistrates and advised them to give orders that the place should be dug up. Bones were found with chains wound round them. Time and the action of the soil had made the flesh moulder, and left the bones bare and eaten away by the chains, but the remains were collected and given a public burial. Ever afterwards the house was free of the ghost which had been thus laid with due ceremony.

2. A Witch Prepares Toil and Trouble

Truth be told, this article could be 100% excerpts from Lucan. This one, which describes a witch gathering ingredients for her potions, stands out as being the most saturated with ghastly imagery (Pharsalia, VI, 529–569; both Latin and English from the Perseus Digital Library).

Viventes animas, et adhuc sua membra regentes,

Infodit busto: fatis debentibus annos

Mors invita subit: perversa funera pompa

Retulit a tumulis: fugere cadavera letum.

Fumantes iuvenum cineres, ardentiaque ossa

E mediis rapit illa rogis, ipsamque, parentes

Quam tenuere, facem: nigroque volantia fumo

Feralis fragmenta tori, vestesque fluentes

Colligit in cineres et olentes membra favillas.

Ast ubi servantur saxis, quibus intimus humor

Ducitur, et tracta durescunt tabe medullae

Corpora; tunc omnes avide desaevit in artus,v

Immersitque manus oculis, gaudetque gelatos

Effodisse orbes, et siccae pallida rodit

Excrementa manus: laqueum nodosque nocentes

Ore suo rupit: pendentia corpora carpsit,

Abrasitque cruces: percussaque viscera nimbis

Vulsit, et incoctas admisso sole medullas.

Insertum manibus chalybem, nigramque per artus

Stillantis tabi saniem, virusque coactum

Sustulit, et nervo morsus retinente pependit.

Et quodcumque iacet nuda tellure cadaver,v

Ante feras volucresque sedet: nec carpere membra

Vult ferro manibusque suis, morsusque luporum

Exspectat, siccis raptura a faucibus artus.

Nec cessant a caede manus, si sanguine vivo

Est opus, erumpat iugulo qui primus aperto.

Nec refugit caedes, vivum si sacra cruorem,

Extaque funereae poscunt trepidantia mensae.

Vulnere sic ventris, non, qua natura vocabat,

Extrahitur partus, calidis ponendus in aris.

Et quoties saevis opus est ac fortibus umbris,

Ipsa facit manes: hominum mors omnis in usu est.

Illa genae florem primaevo corpore vulsit,

Illa comam laeva morienti abscidit ephebo.

Saepe etiam caris cognato in funere dira

Thessalis incubuit membris: atque oscula figens,

Truncavitque caput, compressaque dentibus ora

Laxavit: siccoque haerentem gutture linguam

Praemordens, gelidis infudit murmura labris,

Arcanumque nefas Stygias mandavit ad umbras.

…Men whose limbs were quick

With vital power she thrust within the grave

Despite the fates who owed them years to come:

The funeral reversed brought from the tomb

Those who were dead no longer; and the pyre

Yields to her shameless clutch still smoking dust

And bones enkindled, torches which but now

Some grieving father held, and fragments mixed

In sable smoke and ceremonial cloths

Singed with the redolent fire that burned the dead.

But those who lie within a stony cell

Untouched by fire, whose dried and mummied frames

No longer know corruption, limb by limb

Venting her rage she tears, the bloodless eyes

Drags from their cavities, and mauls the nail

Upon the withered hand: she gnaws the noose

By which some wretch has died, and from the tree

Drags down a pendent corpse, its members torn

Asunder to the winds: forth from the palms

Wrenches the iron, and from the unbending bond

Hangs by her teeth, and with her hands collects

The slimy gore which drips upon the limbs.

Where lay a corpse upon the naked earth

On ravening birds and beasts of prey the hag

Kept watch, nor marred by knife or hand her spoil,

Till on his victim seized some nightly wolf;

Then dragged the morsel from his thirsty fangs;

Nor fears she murder, if some banquet fell

Need blood fresh issued from the gaping throat,

Or panting entrail. By unnatural means

Wombs yield to her the infant to be placed

On glowing altars: and whene’er she needs

Some fierce undaunted ghost, he fails not her

Who has all deaths in use. Her hand has chased

From smiling cheeks the rosy bloom of life;

And with sinister hand from dying youth

Has shorn the fatal lock: and holding oft

In foul embraces some departed friend

Severed the head, and through the ghastly lips,

Held by her own apart, some impious tale

Dark with mysterious horror hath conveyed

Down to the darkness of the Stygian shades.

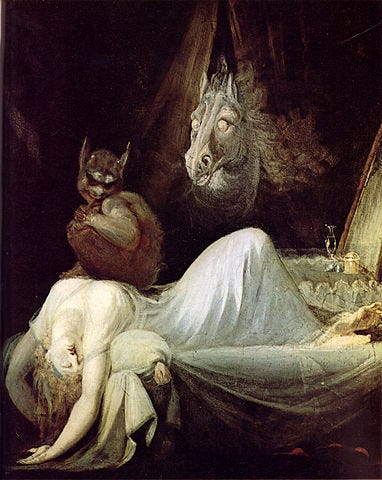

3. A Creeping Incubus

This little passage from Macrobius describing Greek ghouls that haunt sleepers is sure to keep you up at night (Commentary on the Dream of Scipio, I, 3, 7; Latin from a digitized copy from the University of Toronto, English translation courtesy of Gene Cunningham).

φάντασμα vero, hoc est visum, cum inter vigiliam et adultam quietem in quadam, ut aiunt, prima somni nebula adhuc se vigilare aestimans, qui dormire vix coepit, aspicere videtur irruentes in se vel passim vagantes formas a natura seu magnitudine seu specie discrepantes variasque tempestates rerum vel laetas vel turbulentas. In hoc genere est ἐπιάλτης, quem publica persuasio quiescentes opinatur invadere et pondere suo pressos ac sentientes gravare.

A phantasm, that is a “vision”, occurs between wakefulness and deep sleep, in the first fog of sleep, as we say, when the sleeper, who just began to sleep, believing himself still awake, dreams that he sees shapes that differ from natural creatures by size or appearance, as well as various other things, either pleasant or disturbing, coming upon him or wandering here and there. To this category also belongs epialtes, which according to popular belief assails sleepers who feel it pressing and weighing them down.

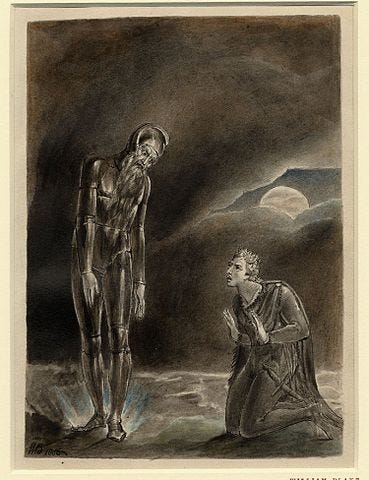

4. A Recipe for Necromancy

This excerpt from Heliodorus explains the process of raising the dead step-by-step, just in case you don’t have any plans for Halloween yet (Theagenes and Chariclea, VI, 14, 1–7; Greek from the TLG, English from Thomas Underdowne, 1587).

Ἡ γὰρ πρεσβῦτις ἀνενοχλήτου καὶ ἀκατόπτου σχολῆς ἐπειλῆφθαι νομίσασα πρῶτα μὲν βόθρον ὠρύξατο, ἔπειτα πυρκαϊὰν ἐκ θατέρου μέρους ἐξῆψε καὶ μέσον ἀμφοῖν τὸν νεκρὸν τοῦ παιδὸς προθεμένη κρατῆρά τε ὀστρακοῦν ἔκ τινος παρακειμένου τρίποδος ἀνελομένη μέλιτος ἐπέχει τῷ βόθρῳ καὶ αὖθις ἐξ ἑτέρου γάλακτος, καὶ οἶνον ἐκ τρίτων ἐπέσπενδεν· εἶτα πέμμα στεάτινον εἰς ἀνδρὸς μίμημα πεπλασμένον δάφνῃ καὶ μαράθῳ καταστέψασα εἰς τὸν βόθρον ἐνέβαλλεν. Ἐφ’ ἅπασι δὲ ξίφος ἀνελομένη καὶ πρὸς τὸ ἐνθουσιῶδες σοβηθεῖσα καὶ πολλὰ πρὸς τὴν σεληναίαν βαρβάροις τε καὶ ξενίζουσι τὴν ἀκοὴν ὀνόμασι κατευξαμένη τὸν βραχίονα ἐντεμοῦσα καὶ δάφνης ἀκρέμονι τοῦ αἵματος ἀποψήσασα τὴν πυρκαϊὰν ἐπεψέκαζεν, ἄλλα τε ἄττα τερατευσαμένη πρὸς τούτοις ἐπὶ τὸν νεκρὸν τοῦ παιδὸς προσκύψασα καί τινα πρὸς τὸ οὖς ἐπᾴδουσα ἐξήγειρέ τε καὶ ὀρθὸν ἑστάναι τῇ μαγγανείᾳ κατηνάγκαζεν. Ἡ Χαρίκλεια δὴ οὖν οὐδὲ τὰ πρῶτα ἀδεῶς κατοπτεύουσα τότε δὴ καὶ ὑπέφριττε καὶ πρὸς τῶν γινομένων ἀήθων ἐκδειματωθεῖσα τὸν Καλάσιριν ἀφύπνιζέ τε καὶ θεατὴν γενέσθαι τῶν δρωμένων παρεσκεύαζεν. Αὐτοὶ μὲν οὖν ἅτε ἐν σκότῳ διάγοντες οὐχ ἑωρῶντο, κατώπτευον δὲ τὰ ἐν τῷ φωτὶ καὶ πρὸς τῇ πυρκαϊᾷ ῥᾷον καὶ τῶν λεγομένων οὐ πόρρωθεν ὄντες ἐπηκροῶντο, τῆς γραὸς ἤδη καὶ γεγωνότερον ἐκπυνθανομένης παρὰ τοῦ νεκροῦ· καὶ ἦν ἡ πεῦσις εἴπερ ὁ ἀδελφὸς μὲν ἐκείνου παῖς δὲ αὐτῆς ὁ λειπόμενος ἐπανήξει περισωθείς. Ὁ δὲ ἀπεκρίνατο μὲν οὐδὲν ἐπινεύσας δὲ μόνον καὶ τῇ μητρὶ τὰ κατὰ γνώμην ἐλπίζειν ἀμφιβόλως ἐνδοὺς κατηνέχθη τε ἀθρόον καὶ ἔκειτο ἐπὶ πρόσωπον. Ἡ δὲ ἐπέστρεφέ τε τὸ σῶμα πρὸς τὸ ὕπτιον καὶ οὐκ ἀνίει τὴν πεῦσιν ἀλλὰ βιαιοτέραις, ὡς ἐῴκει, ταῖς κατανάγκαις πολλὰ τοῖς ὠσὶν αὖθις ἐπᾴδουσα καὶ μεθαλλομένη ξιφήρης ἄρτι μὲν πρὸς τὴν πυρκαϊὰν ἄρτι δὲ ἐπὶ τὸν βόθρον ἐξήγειρέ τε αὖθις καὶ ὀρθωθέντος περὶ τῶν αὐτῶν ἐξεπυνθάνετο, μὴ νεύμασι μόνον ἀλλὰ καὶ φωνῇ τὴν μαντείαν ἀρισήμως δηλοῦν ἐπαναγκάζουσα.

The old woman thinking she had now gotten a time wherein she would neither be seen nor troubled of any, first digged a trench, then made a fire on both sides thereof, and in the midst laid her son’s body. Then taking an earthen pot from a three-footed stool which stood thereby she poured honey into the trench; out of another pot she poured milk, and from the third a libation of wine. Lastly she cast into the trench a lump of dough hardened in the fire, which was made like a man and crowned with a garland of laurel and fennel. This done, she took up a sword which lay among the dead men’s shields, and behaving herself as if she had been in a Bacchic frenzy, said many prayers to the moon in strange outlandish terms. Then she cut her arm and with a branch of laurel besprinkled the fire with her blood; and after doing many monstrous and strange things beside these, at length bowing down to her dead son’s body and saying somewhat in his ear, she awakened him, and by force of her witchcraft made him suddenly to stand. Chariclea, who hitherto had been looking not without fear, trembled with horror and was utterly discomforted by that wonderful sight, so that she awaked Calasiris and caused him also the behold the spectacle. They could not be seen in their dark corner, but they saw easily what she did by the light of the fire, and heard also what she said, for they were not very far off, and the old woman spake very loud to the body. Her question was this: ‘Would his brother, her son who was yet alive, return safe or no?’ The body made no answer, but by nodding gave his mother a doubtful hope of success according to her wish, and then fell down upon its face again. But she turned it over on its back and ceased not to ask that question, with more earnest enforcements, it seemed, speaking in his ear. Sometimes she leapt, sword in hand, to the trench, sometimes to the fire, and at length she made the body stand upright again and asked the same question, compelling him to answer not by nods and becks but plainly by word of mouth.

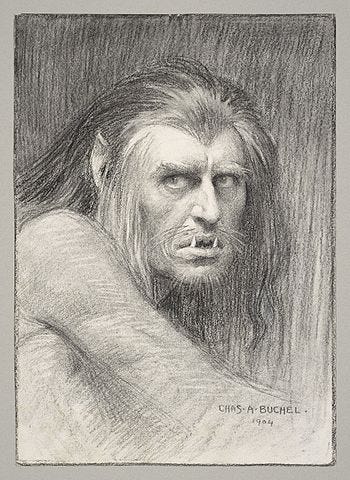

5. A Werewolf Transformation

Petronius describes the moonlit transformation — in a graveyard, of course (Satyricon, 62.1–12; both Latin and English from the Perseus Digital Library).

Venimus intra monimenta: homo meus coepit ad stelas facere, sedeo ego cantabundus et stelas numero. Deinde ut respexi ad comitem, ille exuit se et omnia vestimenta secundum viam posuit. Mihi anima in naso esse, stabam tanquam mortuus. At ille circumminxit vestimenta sua, et subito lupus factus est. Nolite me iocari putare; ut mentiar, nullius patrimonium tanti facio. Sed, quod coeperam dicere, postquam lupus factus est, ululare coepit et in silvas fugit. Ego primitus nesciebam ubi essem, deinde accessi, ut vestimenta eius tollerem: illa autem lapidea facta sunt. Qui mori timore nisi ego? Gladium tamen strinxi et in tota via umbras cecidi, done ad villam amicae meae pervenirem. Ut larua intravi, paene animam ebullivi, sudor mihi per bifurcum volabat, oculi mortui, vix unquam refectus sum […] et postquam veni in illum locum, in quo lapidea vestimenta erant facta, nihil inveni nisi sanguinem. Ut vero domum veni, iacebat miles meus in lecto tanquam bovis, et collum illius medicus curabat. Intellexi illum versipellem esse, nec postea cum illo panem gustare potui, non si me occidisses. Viderint alii quid de hoc exopinissent; ego si mentior, genios vestros iratos habeam.

We got among the tombstones: my man went aside to look at the epitaphs, I sat down with my heart full of song and began to count the graves. Then when I looked round at my friend, he stripped himself and put all his clothes by the roadside. My heart was in my mouth, but I stood like a dead man. He made a ring of water round his clothes and suddenly turned into a wolf. Please do not think I am joking; I would not lie about this for any fortune in the world. But as I was saying, after he had turned into a wolf, he began to howl, and ran off into the woods. At first I hardly knew where I was, then I went up to take his clothes; but they had all turned into stone. No one could be nearer dead with terror than I was. But I drew my sword and went slaying shadows all the way till I came to my love’s house. I went in like a corpse, and nearly gave up the ghost, the sweat ran down my legs, my eyes were dull, I could hardly be revived […] I came to the place where the clothes were turned into stone, I found nothing but a pool of blood. But when I reached home, my soldier was lying in bed like an ox, with a doctor looking after his neck. I realized that he was a werewolf, and I never could sit down to a meal with him afterwards, not if you had killed me first. Other people may think what they like about this; but may all your guardian angels punish me if I am lying.

6. Possession by a Malicious Spirit

Philostratus brings us a sad tale of a young boy possessed by a vengeful presence (Life of Apollonius, III, 38; Greek from the TLG, English from Livius).

καὶ παρῆγε γύναιον ἱκετεῦον ὑπὲρ παιδός, ὃν ἔφασκε μὲν ἑκκαίδεκα ἔτη γεγονέναι, δαιμονᾶν δὲ δύο ἔτη, τὸ δὲ ἦθος τοῦ δαίμονος εἴρωνα εἶναι καὶ ψεύστην. ἐρομένου δέ τινος τῶν σοφῶν, ὁπόθεν λέγοι ταῦτα, ‘τοῦ παιδὸς τούτου’ ἔφη ‘τὴν ὄψιν εὐπρεπεστέρου ὄντος ὁ δαίμων ἐρᾷ καὶ οὐ ξυγχωρεῖ αὐτῷ νοῦν ἔχειν, οὐδὲ ἐς διδασκάλου βαδίσαι ἐᾷ ἢ τοξότου, οὐδὲ οἴκοι εἶναι, ἀλλ᾽ ἐς τὰ ἔρημα τῶν χωρίων ἐκτρέπει, καὶ οὐδὲ τὴν φωνὴν ὁ παῖς τὴν ἑαυτοῦ ἔχει, ἀλλὰ βαρὺ φθέγγεται καὶ κοῖλον, ὥσπερ οἱ ἄνδρες, βλέπει δὲ ἑτέροις ὀφθαλμοῖς μᾶλλον ἢ τοῖς ἑαυτοῦ. κἀγὼ μὲν ἐπὶ τούτοις κλάω τε καὶ ἐμαυτὴν δρύπτω καὶ νουθετῶ τὸν υἱόν, ὁπόσα εἰκός, ὁ δὲ οὐκ οἶδέ με. διανοουμένης δέ μου τὴν ἐνταῦθα ὁδόν, τουτὶ δὲ πέρυσι διενοήθην, ἐξηγόρευσεν ὁ δαίμων ἑαυτὸν ὑποκριτῇ χρώμενος τῷ παιδί, καὶ δῆτα ἔλεγεν εἶναι μὲν εἴδωλον ἀνδρός, ὃς πολέμῳ ποτὲ ἀπέθανεν, ἀποθανεῖν δὲ ἐρῶν τῆς ἑαυτοῦ γυναικός, ἐπεὶ δὲ ἡ γυνὴ περὶ τὴν εὐνὴν ὕβρισε τριταίου κειμένου γαμηθεῖσα ἑτέρῳ, μισῆσαι μὲν ἐκ τούτου τὸ γυναικῶν ἐρᾶν, μεταρρυῆναι δὲ ἐς τὸν παῖδα τοῦτον. ὑπισχνεῖτο δέ, εἰ μὴ διαβάλλοιμι αὐτὸν πρὸς ὑμᾶς, δώσειν τῷ παιδὶ πολλὰ ἐσθλὰ καὶ ἀγαθά. ἐγὼ μὲν δὴ ἔπαθόν τι πρὸς ταῦτα, ὁ δὲ διάγει με πολὺν ἤδη χρόνον καὶ τὸν ἐμὸν οἶκον ἔχει μόνος οὐδὲν μέτριον οὐδὲ ἀληθὲς φρονῶν.’

And he brought forward a poor woman who interceded on behalf of her child, who was, she said, a boy of sixteen years of age, but had been for two years possessed by a devil.

Now the character of the devil was that of a mocker and a liar. Here one of the sages asked, why she said this, and she replied: “This child of mine is extremely good-looking, and therefore the devil is amorous of him and will not allow him to retain his reason, nor will he permit him to go to school, or to learn archery, nor even to remain at home, but drives him out into desert places. And the boy does not even retain his own voice, but speaks in a deep hollow tone, as men do; and he looks at you with other eyes rather than with his own. As for myself I weep over all this and I tear my cheeks, and I rebuke my son so far as I well may; but he does not know me.

And I made my mind to repair hither, indeed I planned to do so a year ago; only the demon discovered himself using my child as a mask, and what he told me was this, that he was the ghost of man, who fell long ago in battle, but that at death he was passionately attached to his wife. Now he had been dead for only three days when his wife insulted their union by marrying another man, and the consequence was that he had come to detest the love of women, and had transferred himself wholly into this boy. But he promised, if I would only not denounce him to yourselves, to endow the child with many noble blessings. As for myself, I was influenced by these promises; but he has put me off and off for such a long time now, that he has got sole control of my household, yet has no honest or true intentions.

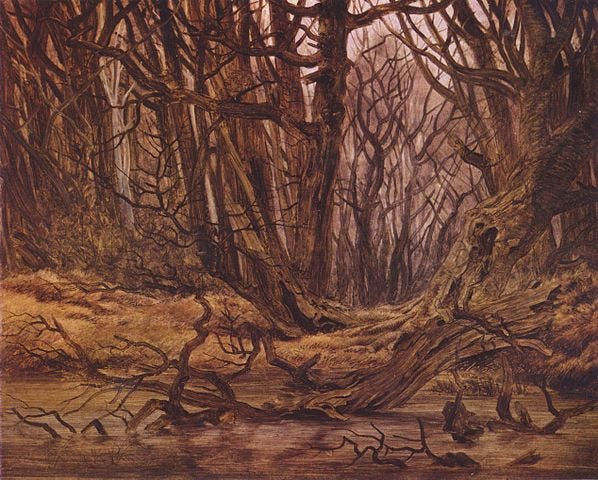

7. A Haunted Wood

I just couldn’t resist including one more Lucan (Pharsalia, III, 399–425; both Latin and English from the Perseus Digital Library). This passage feels like a mixture of The Brothers Grimm and Nathaniel Hawthorne.

Lucus erat longo numquam violatus ab evo,

Obscurum cingens connexis aera ramis,

Et gelidas alte submotis solibus umbras.

Hunc non ruricolae Panes, nemorumque potentes

Silvani Nymphaeque tenent, sed barbara ritu

Sacra deum, structae diris altaribus arae;

Omnisque humanis lustrata cruoribus arbos.

Si qua fidem meruit superos mirata vetustas,

Illis et volucres metuunt insistere ramis,

Et lustris recubare ferae: nec ventus in illas

Incubuit silvas, excussaque nubibus atris

Fulgura: non ullis frondem praebentibus auris

Arboribus suus horror inest. Tum plurima nigris

Fontibus unda cadit, simulacraque moesta deorum

Arte carent, caesisque extant informia truncis.

Ipse situs putrique facit iam robore pallor

Attonitos: non vulgatis sacrata figuris

Numina sic metuunt: tantum terroribus addit,

Quos timeant non nosse deos. Iam fama ferebat

Saepe cavas motu terrae mugire cavernas,

Et procumbentes iterum consurgere taxos,

Et non ardentis fulgere incendia silvae,

Roboraque amplexos circumfluxisse dracones.

Non illum cultu populi propiore frequentant,

Sed cessere deis. Medio cum Phoebus in axe est,

Aut coelum nox atra tenet, pavet ipse sacerdos

Acessus, dominumque timet deprendere luci.

There stood a grove

Which from the earliest time no hand of man

Had dared to violate; hidden from the sun

Its chill recesses; matted boughs entwined

Prisoned the air within. No sylvan nymphs

Here found a home, nor Pan, but savage rites

And barbarous worship, altars horrible

On massive stones upreared; sacred with blood

Of men was every tree. If faith be given

To ancient myth, no fowl has ever dared

To rest upon those branches, and no beast

Has made his lair beneath: no tempest falls,

Nor lightnings flash upon it from the cloud.

Stagnant the air, unmoving, yet the leaves

Filled with mysterious trembling; dripped the streams

From coal-black fountains; effigies of gods

Rude, scarcely fashioned from some fallen trunk

Held the mid space: and, pallid with decay,

Their rotting shapes struck terror. Thus do men

Dread most the god unknown. ’Twas said that caves

Rumbled with earthquakes, that the prostrate yew

Rose up again; that fiery tongues of flame

Gleamed in the forest depths, yet were the trees

Unkindled; and that snakes in frequent folds

Were coiled around the trunks. Men flee the spot

Nor dare to worship near: and e’en the priest

Or when bright Phoebus holds the height, or when

Dark night controls the heavens, in anxious dread

Draws near the grove and fears to find its lord.

8. The Damned

A list of spooky passages in ancient literature would feel a little incomplete without something from Book 6 (Aeneid, VI, 305–330; both Latin and English from the Perseus Digital Library).

Huc omnis turba ad ripas effusa ruebat,

matres atque viri, defunctaque corpora vita

magnanimum heroum, pueri innuptaeque puellae,

impositique rogis iuvenes ante ora parentum:

quam multa in silvis autumni frigore primo

lapsa cadunt folia, aut ad terram gurgite ab alto

quam multae glomerantur aves, ubi frigidus annus

trans pontum fugat, et terris immittit apricis.

Stabant orantes primi transmittere cursum,

tendebantque manus ripae ulterioris amore.

Navita sed tristis nunc hos nunc accipit illos,

ast alios longe submotos arcet harena.

Aeneas, miratus enim motusque tumultu,

“Dic” ait “O virgo, quid volt concursus ad amnem?

Quidve petunt animae, vel quo discrimine ripas

hae linquunt, illae remis vada livida verrunt?”

Olli sic breviter fata est longaeva sacerdos:

“Anchisa generate, deum certissima proles,

Cocyti stagna alta vides Stygiamque paludem,

di cuius iurare timent et fallere numen.

Haec omnis, quam cernis, inops inhumataque turba est;

portitor ille Charon; hi, quos vehit unda, sepulti.

Nec ripas datur horrendas et rauca fluenta

transportare prius quam sedibus ossa quierunt.

Centum errant annos volitantque haec litora circum;

tum demum admissi stagna exoptata revisunt.”

To those dim shores the multitude streams on —

Husbands and wives, and pale, unbreathing forms

Of high-souled heroes, boys and virgins fair,

And strong youth at whose graves fond parents mourned.

As numberless the throng as leaves that fall

When autumn’s early frost is on the grove;

Or like vast flocks of birds by winter’s chill

Sent flying o’er wide seas to lands of flowers.

All stood beseeching to begin their voyage

Across that river, and reached out pale hands,

In passionate yearning for its distant shore.

But the grim boatman takes now these, now those,

Or thrusts unpitying from the stream away.

Aeneas, moved to wonder and deep awe,

Beheld the tumult; “Virgin seer!” he cried, .

“Why move the thronging ghosts toward yonder stream?

What seek they there? Or what election holds

That these unwilling linger, while their peers

Sweep forward yonder o’er the leaden waves?”

To him, in few, the aged Sibyl spoke :

“Son of Anchises, offspring of the gods,

Yon are Cocytus and the Stygian stream,

By whose dread power the gods themselves do fear

To take an oath in vain. Here far and wide

Thou seest the hapless throng that hath no grave.

That boatman Charon bears across the deep

Such as be sepulchred with holy care.

But over that loud flood and dreadful shore

No trav’ler may be borne, until in peace

His gathered ashes rest. A hundred years

Round this dark borderland some haunt and roam,

Then win late passage o’er the longed-for wave.”

9. Battlefield Apparitions

If you are feeling a little unnerved by the first 8 stories, you may find comfort in Cassius’s words to Brutus below (Plutarch, Life of Brutus, 36.3–37.3; both Greek and English from the Perseus Digital Library).

ὡς οὖν ἔμελλεν ἐξ Ἀσίας διαβιβάζειν τὸ στράτευμα, νὺξ μὲν ἦν βαθυτάτη, φῶς δ᾽ εἶχεν οὐ πάνυ λαμπρὸν ἡ σκηνή, πᾶν δὲ τὸ στρατόπεδον σιωπῇ κατεῖχεν. ὁ δὲ συλλογιζόμενός τι καὶ σκοπῶν πρὸς ἑαυτόν ἔδοξεν αἰσθέσθαι τινὸς εἰσιόντος, ἀποβλέψας δὲ πρὸς τὴν εἴσοδον ὁρᾷ δεινὴν καὶ ἀλλόκοτον ὄψιν ἐκφύλου σώματος καὶ φοβεροῦ, σιωπῇ παρεστῶτος αὐτῷ. τολμήσας δὲ ἐρέσθαι, ‘τίς ποτ᾽ ὢν,’ εἶπεν, ‘ἀνθρώπων ἢ θεῶν, ἢ τί βουλόμενος ἥκεις ὡς ἡμᾶς;’ ὑποφθέγγεται δ᾽ αὐτῷ τὸ φάσμα: ‘ὁ σὸς, ὦ Βροῦτε, δαίμων κακός: ὄψει δέ με περὶ Φιλίππους.’ καὶ ὁ Βροῦτος οὐ διαταραχθεὶς, ‘ὄψομαι,’ εἶπεν. ἀφανισθέντος δ᾽ αὐτοῦ τοὺς παῖδας ἐκάλει: μήτε δ᾽ ἀκοῦσαί τινα φωνὴν μήτ᾽ ἰδεῖν ὄψιν φασκόντων, τότε μὲν ἐπηγρύπνησεν: ἅμα δ᾽ ἡμέρᾳ τραπόμενος πρὸς Κάσσιον ἔφραζε τὴν ὄψιν. ὁ δὲ τοῖς Ἐπικούρου λόγοις χρώμενος καὶ περὶ τούτων ἔθος ἔχων διαφέρεσθαι πρὸς τὸν Βροῦτον, ‘ἡμέτερος οὗτος,’ εἶπεν, ‘ὦ Βροῦτε, λόγος, ὡς οὐ πάντα πάσχομεν ἀληθῶς οὐδ᾽ ὁρῶμεν, ἀλλ᾽ ὑγρὸν μέν τι χρῆμα καὶ ἀπατηλὸν ἡ αἴσθησις, ἔτι δ᾽ ὀξυτέρα ἡ διάνοια κινεῖν αὑτὸ καὶ μεταβάλλειν ἀπ᾽ οὐδενὸς ὑπάρχοντος ἐπὶ πᾶσαν ἰδέαν. κηρῷ μὲν γὰρ ἔοικεν1 ἡ τύπωσις, ψυχῇ δ᾽ ἀνθρώπου, τὸ πλαττόμενον καὶ τὸ πλάττον ἐχούσῃ τὸ αὐτό, ῥᾷστα ποικίλλειν αὑτὴν καὶ σχηματίζειν δι᾽ ἑαυτῆς ὑπάρχει, δηλοῦσι δὲ αἱ κατὰ τοὺς ὕπνους τροπαὶ τῶν ὀνείρων, ἃς τρέπεται τὸ φανταστικόν ἐξ ἀρχῆς βραχείας παντοδαπὰ καὶ πάθη καὶ εἴδωλα γινόμενον. κινεῖσθαι δ᾽ ἀεὶ πέφυκε: κίνησις δ᾽ αὐτῷ φαντασία τις ἢ νόησις. σοὶ δὲ καὶ τὸ σῶμα ταλαιπωρούμενον φύσει τὴν διάνοιαν αἰωρεῖ καὶ παρατρέπει. δαίμονας δ᾽ οὔτ᾽ εἶναι πιθανόν οὔτε ὄντας ἀνθρώπων ἔχειν εἶδος ἢ φωνὴν ἢ δύναμιν εἰς ἡμᾶς διήκουσαν: ὡς ἔγωγ᾽ ἂν ἐβουλόμην, ἵνα μὴ μόνον ὅπλοις καὶ ἵπποις καὶ ναυσὶ τοσαύταις, ἀλλὰ καὶ θεῶν ἀρωγαῖς ἐπεθαρροῦμεν, ὁσιωτάτων ἔργων καὶ καλλίστων ἡγεμόνες ὄντες.’ τοιούτοις μὲν ὁ Κάσσιος ἐπράϋνε λόγοις τὸν Βροῦτον.

Once, accordingly, when he was about to take his army across from Asia, it was very late at night, his tent was dimly lighted, and all the camp was wrapped in silence. Then, as he was meditating and reflecting, he thought he heard some one coming into the tent. He turned his eyes towards the entrance and beheld a strange and dreadful apparition, a monstrous and fearful shape standing silently by his side. Plucking up courage to question it, “Who art thou,” said he, “of gods or men, and what is thine errand with me?” Then the phantom answered “I am thy evil genius, Brutus, and thou shalt see me at Philippi.” And Brutus, undisturbed, said: “I shall see thee.”

When the shape had disappeared, Brutus called his servants; but they declared that they had neither heard any words nor seen any apparition, and so he watched the night out. As soon as it was day, however, he sought out Cassius and told him of the apparition. Cassius, who belonged to the school of Epicurus, and was in the habit of taking issue on such topics with Brutus, said: “This is our doctrine, Brutus, that we do not really feel or see everything, but perception by the senses is a pliant and deceitful thing, and besides, the intelligence is very keen to change and transform the thing perceived into any and every shape from one which has no real existence. An impression on the senses is like wax, and the soul of man, in which the plastic material and the plastic power alike exist, can very easily shape and embellish it at pleasure. This is clear from the transformations which occur in dreams, where slight initial material is transformed by the imagination into all sorts of emotions and shapes. The imagination is by nature in perpetual motion, and this motion which it has is fancy, or thought. In thy case, too, the body is worn with hardships and this condition naturally excites and perverts the intelligence. As for genii, it is incredible either that they exist, or, if they do exist, that they have the appearance or the speech of men, or a power that extends to us. For my part, I could wish it were so, in order that not only our men-at‑arms, and horses, and ships, which are so numerous, but also the assistance of the gods might give us courage, conducting as we do the fairest and holiest enterprises.” With such discourse did Cassius seek to calm Brutus.

Sign up to receive email updates about new articles

Comment

Sign in with