"Away Hector Fled in Fear": Homer's Humanization of War

Hollywood Deifies Its Heroes: Homer Makes His Human

[Editor’s Note: This was one of two prizewinning essays in the 2018 Paideia Institute High School Essay contest. We are pleased to publish here the essay of the Greek winner, Kim Montpelier. Kim won a trip to Greece for Living Greek in Greece 2018.]

ὣς ὅρμαινε μένων, ὃ δέ οἱ σχεδόν ἦλθεν Ἀχιλλεύς

ἶσος Ἐνυαλίῳ κορυθάϊκι πτολεμιστῇ

σείων Πηλιάδα μελίην κατὰ δεξιόν ὦμον

δεινήν: ἀμφί δέ χαλκός ἐλάμπετο εἴκελος αὐγῇ

ἢ πυρός αἰθομένου ἢ ἠελίου ἀνιόντος.

Ἕκτορα δ᾽, ὡς ἐνόησεν, ἕλε τρόμος: οὐδ᾽ ἄρ᾽ ἔτ᾽ ἔτλη

αὖθι μένειν, ὀπίσω δέ πύλας λίπε, βῆ δέ φοβηθείς.

(Homer: The Iliad, Book 22, lines 131 to 137)

“But Achilles was closing in on him now, like the god of war, the fighter’s helmet flashing, over his right shoulder shaking the Pelian ash spear, the terror and the bronze around his body flared like a raging fire or the rising, blazing sun. Hector looked up, saw him, started to tremble, nerve gone, he could hold his ground no longer, he left the gates behind and away he fled in fear.” (Translated by Robert Fagles)

After surviving the firebombing of Dresden in World War II, Kurt Vonnegut wrote Slaughterhouse 5, an anti-war book about an author struggling to write about the war. In the story, Vonnegut visits an old war friend, Bernard O’Hare, to exchange anecdotes from the war. As they recall old stories, O’Hare’s wife, Mary, grows angry and explains that Vonnegut is going to write a great war story about brave heroes who will be played by Frank Sinatra and John Wayne when it is turned into a movie. Her point was that they were not heroes, but just scared young men fighting other scared young men. The relevance to today’s world of fearless teenage heroes and James-Bond-type protagonists is startling. War is not portrayed as the terrible act it is; rather, it is rubbed with sandpaper and given a polished finish. However, in contrast, the Iliad provides a raw and human story of war. This is exemplified when Hector, the best of the Trojans, flees from god-like Achilles, simply because he is afraid. It is important for people to read and consider this in order to understand how war is glorified today and how detrimental and corrosive that is to society.

Firstly, war is turned into a battle of good versus evil. For every hero there is a villain. Batman against the Joker. Harry Potter against Lord Voldemort. Light against Dark. The good side is purely good, the evil side is dehumanized. This delineation of good and bad rarely happens in real life. Both sides often have validity. For example, in an eyewitness account, Victor Tolley, an American marine during World War II deployed to Nagasaki after the dropping of the atomic bomb, described his hatred for the Japanese because he was programmed to hate his enemy. However, on speaking with a Japanese family, Tolley realized that they had both experienced the same amount of suffering. This is a prime example of the dehumanization of the enemy, and humanity being washed out of war. On the other hand, the Iliad is so unbiased that at the scene of Hector’s flight, it is impossible to definitively declare Achilles or Hector as the “good guy.” Both are simply men with grievances, fighting for their cause, as it is in real life. As Hector stands his ground, thinking of how to reason with Achilles, and then realizes that he simply cannot win, the reader feels a great remorse for him. Simultaneously, Achilles wants justice for his best friend who has just been killed, an emotion all can sympathize with. There is no defined villain in this. Hector’s flight in the Iliad is important because it refuses to simplify a war between men and instead embraces the validity of both sides, as we so often neglect to do.

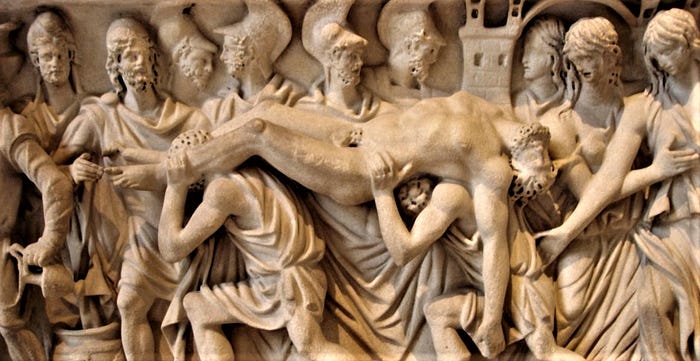

Secondly, war is glorified today through the portrayal of soldiers as fearless heroes in our prized stories. Harry Potter, for example, only a teenager, never fled from battle against Lord Voldemort, one of the most powerful wizards of all time. Frodo Baggins, an average hobbit, goes on a quest where dangerous enemies aim to kill him every step of the way. Our heroes are not even given the freedom to choose to flee. We so highly value courage that we cannot handle the disappointment of our heroes making the decision to run away, even if it is the right decision. This is possible because our heroes are invulnerable — we know they will not die. The reality of war is that, most often, people are killed randomly, and that who they are outside of the war is not taken into account when they are being attacked. People fighting for their lives should be scared. Not only does the Iliad challenge this notion that heroes in war must always be courageous, it goes a step further in that the heroes can and do die. Before the battle, Hector thinks of bargaining, bribing, and reasoning with Achilles. When he accepts that none of these tactics will work, he prepares to fight. He is ready until he sees Achilles, “closing in on him now, like the god of war, the fighter’s helmet flashing, over his right shoulder shaking the Pelian ash spear,” and suddenly runs away. He knows he is going to die because he is going up against a man who is half-divine. Not only does he know he cannot win, he also does what none of our heroes have the guts to do: he accepts it. Afraid for his life, and what his death would mean for his family, man-killing Hector runs away. He is the underdog who does not win, and it is better that way because it is real. This is important because when we neglect to show that heroes can have fear in truly fearful situations, we gloss over the real aspects of war, and make it seem better than it is.

When the ugliness of war is overlooked — or, worse, the portrayal of war is falsified — when people are taught to personally hate the enemy, when soldiers look invulnerable, this is glorification in overdrive. When the atrocities of war are left out from the narrative, say, the horrifying cases of trench foot from World War I, the fifty million people who lost their lives in World War II, not to mention famine and disease, war does not seem so bad. As a result, what Mary O’Hare said was true: “War will look just wonderful, so we’ll have a lot more of them. And they’ll be fought by babies.” While the Iliad does not include all of these atrocities, it does well in portraying the human fears that are felt in a war, even by the best fighters. If we as a society can succeed in rectifying how we look at war, perhaps the world might become a slightly more peaceful place.

Kim Montpelier is a student at the Washington Latin Public Charter School, and a winner of the Paideia Institute High School Essay contest.

Sign up to receive email updates about new articles

Comment

Sign in with