Caesar's Gone Since 44 BC, But Latin Lives!

John Roos and the Legacy of Keeping Latin Alive in Culver, Indiana

CULVER, INDIANA — Up the road where J. and I take our daily walks there’s an eclectic neo-Georgian style home on a hill with a large porch and a three-car garage, a kind of Hoosier villa nestled in the woods.

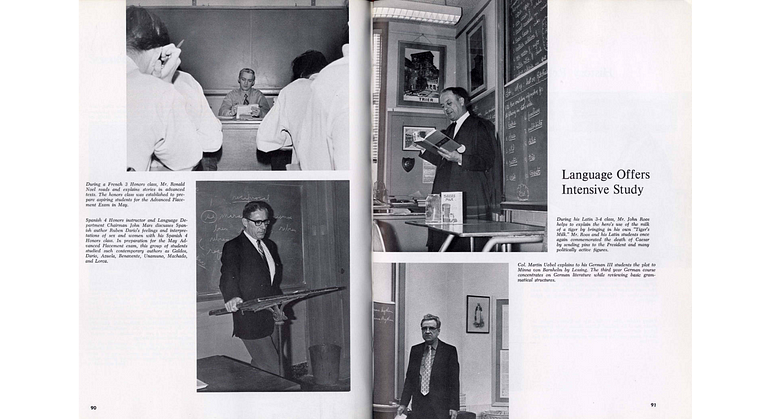

It’s an Academy Guest House now, but it once belonged to Mr. John Roos, one of the most remarkable Latin teachers this country has ever produced. Roos was long-time Instructor in Latin at the Academy (1941–1971), who left behind a colorful, lasting legacy of teaching excellence, sound and innovative pedagogy, and devotion.

The Roos House, Culver, Indiana (May 2020, my photograph)

The Roos House, Culver, Indiana (May 2020, my photograph)His home, set back in an idyllic pastoral landscape, once had a handsome black and white sign which gave his address in Latin style: “The ROOS Family: CCCC VIA DUODEVICESIMA (400 West 18th Road).”

Roos brought fame to Culver Military Academy’s Latin program with an enterprising national marketing campaign. On March 15, 1969, he took out an obituary for Julius Caesar in The New York Times and an additional 26 US newspapers. As part of this media blitz he had thousands of pink and white buttons made that read “The Latin students of Culver Military Academy say: CAESAR’S GONE SINCE 44 B.C., BUT LATIN LIVES.” According to the Princeton Alumni Weekly (Vol. 71, p. 20; Roos graduated from Princeton in 1929), Roos accompanied this PR showmanship with sound active, engaged pedagogy: he staged a debate on the Ides of March, where students took sides for and against Caesar’s totalitarian rule, his historically violent (some would argue genocidal) expedition into Gaul, and his ultimate assassination at the hands of republican senators: Pro Caesare, In Caesarem?

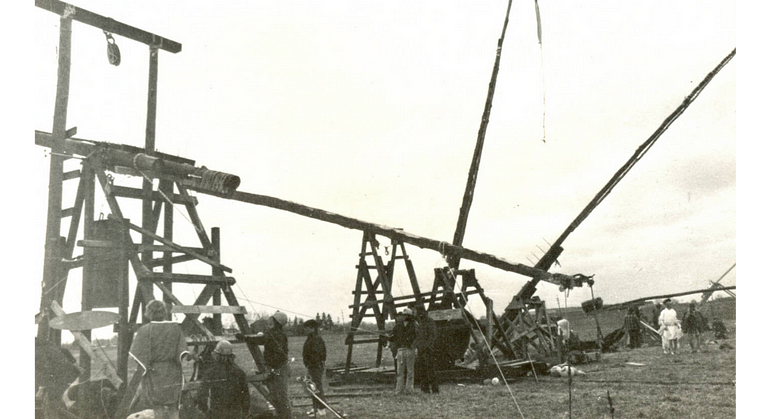

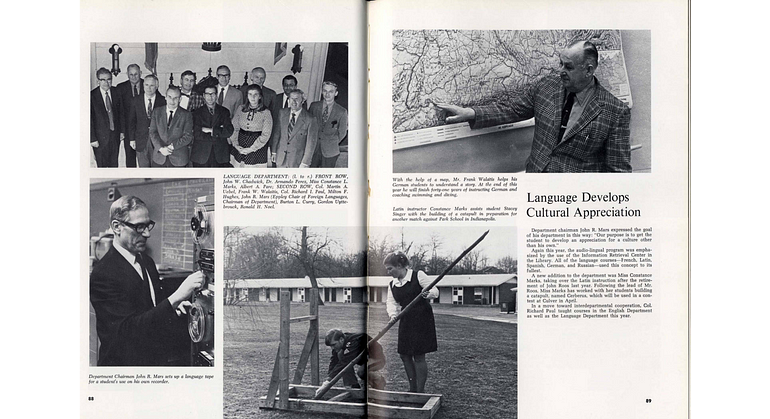

Roos’s most famous publicity stunt, however, took the form of a fanciful Roman catapult contest that caught the eye of national television producers.

In 1971, the Ides of March in Culver saw the arrival of a New York film crew from NBC’s First Tuesday program, a nationally broadcast competitor against CBS’s 60 Minutes. The cameras rolled to capture a catapult distance duel between John Roos’s Culver Latin students and those of the Park School in Indianapolis (led by Bernard Barcio, co-creator of the tournament). (Footage covering both Culver’s and Park School’s catapult teams can be found here).

The catapult contest had its origins in 1967, when “Culver’s Latin students, represented by a young alumnus, laid a wreath on Caesar’s statue in Rome, an act which gained world-wide attention and fanned Mr. Roos’ imagination” (Culver Alumnus, Winter 1971). The Associated Press’s Rome bureau took a photograph of the event, and it subsequently received more coverage in Europe and throughout the United States than any other single item out of that bureau during 1967.

In 1968, Gregory Marshall, another Roos student, dressed in Roos’s own Roman general’s costume (Roos purchased it in Rome in the summer of 1964) “mounted on a noble steed (from Culver’s horsemanship department, of course), re-enacted Caesar’s famous crossing of the Rubicon (Roos made use of northern Indiana’s Yellow River)” (Culver Alumnus 1969). (Follow the link to a 1972 video of John Roos in his full Roman costume.)

By 1971 the NBC crew was among the many media representatives who would flock to Culver to cover what became an annual contest, at its peak drawing catapult contestants from across the State of Indiana. The annual spectacle grew into a collaborative, hands-on learning event for the entire Culver campus, as the work involved in building accurate, large-scale Roman-era catapults required large numbers of student volunteers, faculty assistance (physics instructors engineered the structures), and craftsmen from Culver’s Facilities Department. And still more: it was Culver’s Public Relations department that officially pitched the project to NBC in April of 1970.

Roos, who died in 1977, joined the Academy’s Foreign Language Department in 1941 and taught to his retirement in 1971. While fondly remembered for his theatrics and his keen sense of the power of spectacle (all of which aimed to bring excitement and attention to an academic discipline too often obscured by stodgy pedantry), he leaves a deeper, more lasting legacy.

Roos in the 1933 Culver Alumnus

Roos in the 1933 Culver Alumnus

“Roos left perhaps his most enduring influences in his Latin classroom… A former student of his recalls a prophetic quote from Vergil inscribed on a poster which hung in that Latin room: Forsan et haec olim meminisse iuvabit. ‘Perhaps even this, someday, we will rejoice to remember.’” (Culver Alumni 1978; for more on this famous phrase, see Danielle Bostick’s 2019 piece in this journal.)

Among those recalling Roos’s classroom demeanor in the article was John Houghton, who went on to become a decorated academic and a member of the Episcopal priesthood, who said of his former instructor, “He could be as comic as Plautus and Terence, just as he could be dignified with Cicero or majestic with Vergil.”

Another remembrance, from Howard Waugh, noted other ways Roos kept students active and engaged:

In his classroom we shamelessly spoke Latin as best we could, and though none of us were fluent, we often quoted Caesar (or Virgil) as the case might be, to illustrate our points, and though he corrected our errors, he did it in a way that reflected his pride in our humble achievements and encouraged us to do better.

John’s boundless enthusiasm for Rome and the Latin language brought the subject “alive” for us and turned a potentially dull and turgid subject into a true adventure. How I wish my University professors had had a small measure of his creativity in presentation.

This deeper legacy is one of sound, engaging, student-centered teaching. Not only did Roos leave a lasting legacy of the possibility for a hands-on, experiential Latin teaching method, but Roos’s pioneering pedagogy included speaking in Latin well before it had established itself as widespread teaching practice in North American Latin classrooms.

Former Culver superintendent, the late John Mars, said of his friend at his passing: “John Roos was one of the most saintly men I have known. In thirty-seven years, I never heard John make one critical remark of anyone. He was exemplary.” For many Culver alumni/ae, he became the principal reason to remember the Ides of March.

Epilogue: Student-centered Latin pedagogy and Culver Academies Latin Today

What would such an active, immersive, student-centered Latin pedagogy look like today? And how far should we follow in Roos’s footsteps? (He did, after all, dress up like Caesar in front of his students — a deeply divisive and controversial figure in any era.) In other words: What do we learn from Roos? What do we change and adapt?

Roos was exemplary in his commitment to teaching for his students — not simply to them. He understood well that as teachers we have not just “content mastery” or “skill acquisition” or “job readiness” as our goal for student learning, but we have in fact the long-term happiness and flourishing of our students as our final aim. This means that we meet our students where they are (which is more radical than it sounds) and we encourage them, empower them, and affirm them however we can (and however works!). We show them that a world in which they can flourish is possible and is on the horizon.

Latin educators — any educator, really — should draw on this foundational principle in Roos’s teaching. Affirmation.

Superintendent Mars remarked above that Roos was “one of the most saintly” people he had ever known. Waugh that he encouraged his students to speak Latin shamelessly, that he always corrected errors in a way that helped students know that he was proud of them. He always encouraged his students, and coupled, as Houghton wrote, seriousness with his sense of humor. Affirmation is one of the most powerful resources in a teacher’s teaching practice, and can make the difference between encouraging a student well beyond your classroom and turning them from you forever.

Roos understood well, too, the importance of student participation (not just cooperation), of a gripping pedagogy, of a story for his students. In other words: Engagement.

Waugh, again, writes above that Roos brought Latin alive, and took a “potentially dull and turgid” class into an “adventure.” We needn’t have Roos’s special sense for marketing and timely spectacle, but we do need something like Roos’s commitment to engage his students. To realize that engaging students who may very well be skeptical of the worth of their Latin studies is decidedly not to “dumb down” the subject, but to make it a class for them (the people who make up the class!). Roos, I’m sure, didn’t leave Princeton thinking he’d run a catapult contest in Northern Indiana someday; but when we’re willing to engage our students in ways they find gripping, we’re often drawn down untrod paths.

Last, Roos knew for everything he did to encourage students to study the Romans, their story was complex and fraught with deep moral and political incongruence. He didn’t shy away from this. As much as he used Caesar as a playful marketing tool for the Academy’s Latin program, he knew his legacy demanded careful examination. He engaged his students in debate — pro or con for Caesar? — knowing that history isn’t as simple as the memory of those who dominate. To use a bit of teacher lingo: he taught deeply. Behind the surface drama of a Roos class was a commitment to teaching and learning about Latin and Romans in a way that was both engaging and accurate. Depth.

In sum: Many things have changed (and have needed to) since Roos retired in 1971, but many pedagogical principles in our program at the Culver Academies remain the same. My colleague, Ashley Brewer, and I still aim to teach with affirmation, (keen) presentation, and depth. These help keep Latin alive for our students. But the past 50 years have also seen tremendous change, and we embrace the changes this has effected in our teaching.

We teach in a proficiency-oriented, progressive Latin curriculum that Brewer first codified in Fall 2018 (when I joined the Department of World Languages and Cultures). We speak, read, and write Latin with our students every day. We draw from dynamic, exciting online conversations surrounding Comprehensible Input in the Latin classroom, and strive to make our program in line with the latest Second Language Acquisition research. We teach Ancient Mediterranean Cultures intentionally and critically, engaging our students in discussion and research surrounding race, class, sexual orientation, gender identity, slavery, and war in the ancient world. We have a prominent display of classicists of color on one of the front walls of our classroom. We do this all with the aim of welcoming every Latin student into a classroom culture of inclusion, growth, excitement, empathy, and empowerment.

These aims now enter into a new era. This past spring we taught actively via Zoom, refining our practices, re-imagining just what our Latin instruction looks like on the internet. We aimed to cultivate welcoming online spaces where students can grow, learn, and lead. Most important, we’re caring for our students first, seeing what touches them, excites them, and makes them curious.

Just as Roos aimed to bring Latin alive — to make a possibly “turgid” subject into a “true adventure” (by whatever means necessary!) — we too hope to carry on Latin instruction at Culver into a new century with excitement and vitality. We also proudly continue to speak Latin “shamelessly.”

Latin lives at the Culver Academies. Were “Mr. Roos” still with us — were he, too, working from home, juggling conflicting commitments of family and job at the very same desk; were he, too, so deeply uncertain of what just might come next; were he, too, learning to teach Latin at a distance, when we’ve for so long associated Latin instruction with special classroom connections between students and instructors — I think we know what he would say.

Forsan et haec olim meminisse iuvabit.

Portions of this article originally appeared in the online magazine of Culver Academies History on March 9, 2016. Reprinted by permission. Jeff Kenney, “The Ides of March, Culver style: John Roos’ catapult wars”. https://www.facebook.com/notes/culver-academies-history/the-ides-of-march-culver-style-john-roos-catapult-wars/991083607608301

Jeff Kenney is Archives Manager and Curator at the Culver Academies Museum.

Evan Dutmer, Ph.D., is Instructor in Latin, Ancient Mediterranean Cultures, and Ethics at the Culver Academies, where Ashley Brewer also serves as Senior Instructor in Latin and Ancient Mediterranean Cultures.

Sign up to receive email updates about new articles

Comment

Sign in with