Obelisk Metropolis

The Largest of Rome’s Obelisks Weighs Over 400 Tons, and Had to Be Brought 1700 Miles From Egypt — But Most Tourists Barely Notice Them

There are two ways to look at obelisks. One is out of your peripheral vision as you scurry to your primary destination. Rome has 13 obelisks, more than any other city in the world, so there are plenty to rush by. The other is to experience them like geologist Alex Julien and recognize they have a story to tell. He wrote in an 1893 article in the Journal of the American Geographical Society of New York, “Out under the open sky, therefore, should the old monolith fitly stand for all time, to tell us this story.”

I was a peripheral-vision scurrier until I returned Rome in March for the first time in two decades. I had only even seen obelisks on the way to other monuments I once considered more impressive. With all of the iconic structures in Rome, it is easy to take the obelisks for granted. My obelisk apathy ended when my husband stopped in front of the Montecitorio Obelisk, which now stands with little fanfare in front of the Chamber of Deputies, a location that hardly invites marveling. Nonetheless, he marveled at its size and wondered aloud how in the world the Romans transported it from Egypt to Rome.

My husband’s interest in the obelisk sparked my interest. Was I missing something all of these years? Yes, I was. I spent many insomnia-fueled nights reading everything from Pliny the Elder to the Journal of Nautical Archaeology. Every aspect of obelisks, from their birth to present day condition, is miraculous.

Centuries before the Romans conquered Egypt, obelisks were quarried and extracted in a single piece, then transported on specially-designed barges on the Nile to stand in pairs in front of temples, “mute stone guards bearing triumphant inscriptions,” according to Anthony Grafton in The American Scholar.

In 10 BC, Augustus expatriated the Montecitorio Obelisk from Egypt, where it had stood since the reign of Psametik II (595–589 BC). The technology behind the transportation of obelisks from Egypt to Rome remains somewhat of a mystery. We know that Egyptians used barges to transport the obelisks on the Nile, but a different kind of vessel was necessary for navigation over the Mediterranean. Pliny refers to a single obelisk ship, while modern scholar Armin Wirsching has hypothesized that it would require several ships working in concert.

Even modern examples of obelisk transportation seem complicated and arduous. In 1877, during the transport of one of “Cleopatra’s Needles” from Egypt to London, the obelisk was nearly lost and several seamen perished in a storm. The account from the Sunday, October 21, 1877 edition of the New York Times describes the ordeal and challenges of the voyage:

At daylight it was blowing a living gale of wind, with a heavy sea, the obelisk steering wildly and laboring heavily. Her commander kept her on her course, which was a little east of north, by the compass, but the extreme length of the obelisk prevented her from rising readily to the sea, and she was several times completely swept by the heavy seas that boarded her on the quarter. By inserting their fingers and toes in the hieroglyphics, the crew managed to save themselves…

The great weight of the obelisk’s stern had a tendency to keep her pyramidal bow out of water, and though this was an advantage so long as she was scudding, it increased the difficulty of bringing her head to the wind.

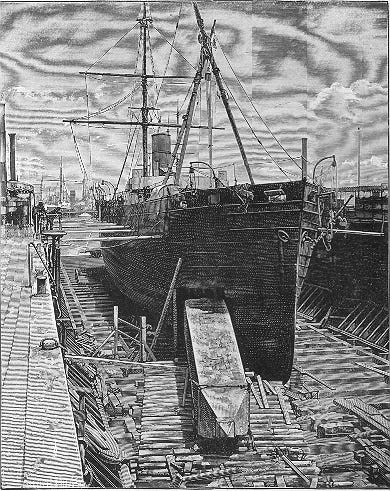

The piece prompted the author of this article to write, “To transport the mountain would be almost as easy to transport the obelisk.” Despite the near-loss of the obelisk destined for London, in 1881, a second of Cleopatra’s Needles, was transported by an awkwardly customized ship, the SS Desoug from Egypt to New York City. Even with the technology available in 2005, when Italy agreed to repatriate the Obelisk of Axum, it had to be cut into three pieces and flown in three trips to Ethiopia.

In ancient Rome, the transportation of obelisks was not just a practical task. Rather, it was testament to Rome’s mastery over both the manmade and the natural, an accomplishment worthy of celebration. According to Pliny the Elder, obelisk ships were put on display and heralded as “more miraculous than anything else on the sea.”

Eventually, the Montecitorio Obelisk arrived to Rome after its journey across the Mediterranean sea on an obelisk ship and then up the Tiber on a barge. Transporting the obelisk from the river to its position on the Campus Martius was also difficult. For perspective, once Cleopatra’s Needle arrived at 96th Street on the Hudson River in 1881, it took 112 days to transport it south to 82nd Street and into Central Park where it now stands, a painstaking process described in a 1997 New York Times article.

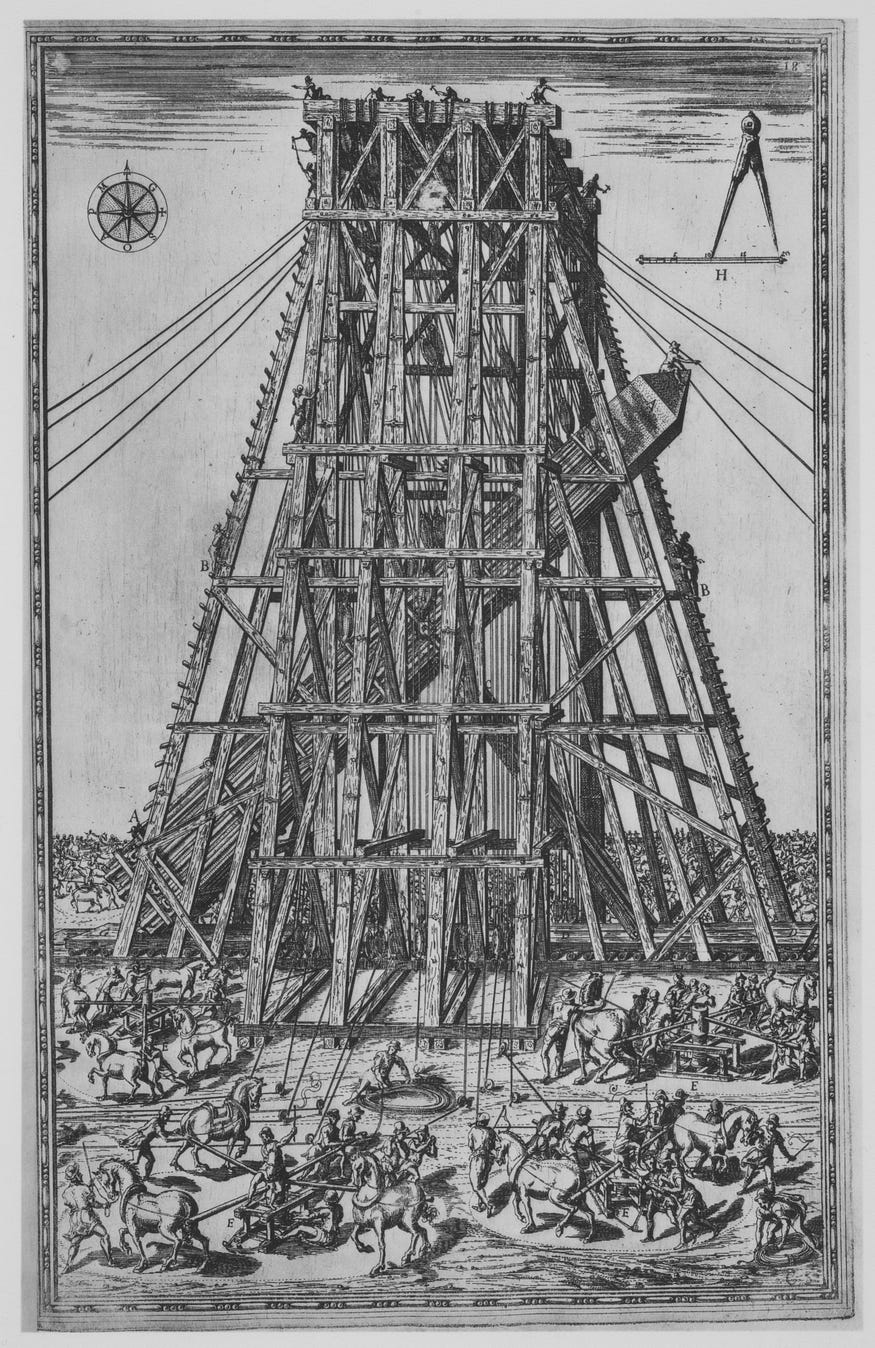

Even moving an obelisk a few hundred yards requires tremendous skill and manpower. In 1585, Pope Sixtus V decided the obelisk that once served as the spina of the Circus of Nero would be the ideal centerpiece for Vatican Square, a plan that required the obelisk to be moved 250 yards. Architect Domenico Fontana, the architect of St. Peter’s, was selected from a pool of 500 mathematicians, architects, and engineers. The task required 907 men, 75 horses, and 40 cranes.

As the Montecitorio Obelisk was ready to be installed, Augustus created a base for it with an inscription that celebrated his conquest of Egypt:

Imp Caesar Divi F Augustus… Aegypto in potestatem populi Romani redacta soli donum dedit.

Emperor Augustus, son of Divine Caesar, dedicated (it) to the sun after bringing Egypt under the power of the Roman people.

He then positioned the stone to cast a shadow in the direction of the Ara Pacis and to serve as the gnomon of a meridian, a device used to mark noontime and help align the civil and solar calendars. If you connected the dots between it, the Ara Pacis, and his mausoleum, the trio of monuments formed a right triangle, which, according to Peter Heslin, represented a triumvirate of sorts: the defeat of Antony, the passing of Lepidus, and the transformation of Octavian to Augustus.

The meridian ceased to function decades after its construction and was eventually recalibrated by Domitian, who like his predecessors, was responsible for regulating the calendar in his role as Pontifex Maximus. By ensuring the accuracy of the civil calendar, Domitian associated himself with Augustus and distanced himself from the chaos that marked Nero’s reign.

Eventually, the drama of the original complex was lost to time. The Ara Pacis now sits in a different location on the Campus Martius, and Augustus’ mausoleum, which is finally undergoing a much-needed renovation after sitting overgrown with weeds and strewn with trash for far too many decades. Eventually, the obelisk fell, was encased in centuries of mud, and was finally discovered, burnt and broken, during the Renaissance. It was re-erected in its present location — the one I used to rush past on my way to what I then perceived to be more important things — in 1792 by Pope Pius VI.

Each obelisk has a story to tell. When we encounter one, we should listen.

For (the Egyptians) worship was that of the Sunbeam- the token of all that was brightest in human life and hope. What more fitting emblem of this idea could the Egyptian set up — what more worthy of our sympathy and reverence — than the Obelisk — a towering shaft of ruddy stone, like the first beam of rosy light which flashes up from the daybreak? — Alex Julien

Sign up to receive email updates about new articles

Comment

Sign in with