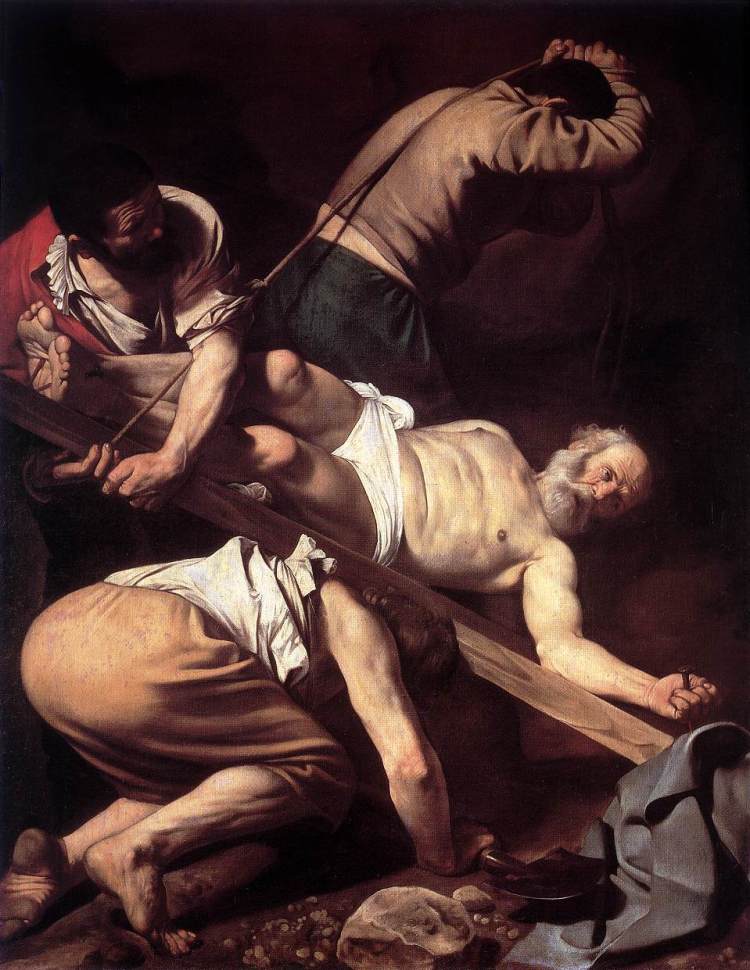

Just inside the unassuming Chiesa di Santa Maria del Popolo lie two, slightly obscured, masterpieces of the Baroque era. In fact, you might not even know they existed, were it not for the hordes of tourists twisting their necks to see them. Neither piece takes the central position over the altar in the Cerasi Chapel.1 As you look up to the left, you see the striking image of Saint Peter’s crucifixion portrayed by the Baroque painter, Caravaggio.

The painting’s immediate features are enough to stun any viewer. Caravaggio’s renowned use of chiaroscuro (the dramatic shift from light to dark) places Peter’s particularly bedraggled body and troubled expression in the spotlight, while dimming our view of his executioners’ faces. Caravaggio’s brutally naturalistic depiction of St. Peter marks a drastic departure from Michelangelo’s idealistic figures. And then we have the drama of the scene itself: A crucified man is being turned upside down. Caravaggio shows his figures in the midst of the action and deliberately places each gruesome, straining muscle in the foreground – including one man’s behind. Peter himself appears more like the working man than a saint. Perhaps most puzzling to the viewer is Peter’s emotional state. Is his a face of anguish, determination, or something else?

As in many of Caravaggio’s signature works, the moment portrayed here is transitory. While Peter’s legs are being raised, he is clearly straining to keep his head upright. This tension may be a physical rendering of Peter’s ambiguous expression – perhaps he is not yet fully committed to his choice. In the Acta Petri, an apocryphal account of Peter’s acts, we are told that while Peter was fleeing persecution on the Via Appia, he had a vision of Jesus Christ:2

“ut autem portam civitatis voluit egredi, visit sibi Christum occurrere. et adorans eum ait; Domine, quo vadis? Respondit ei Christus: Romam venio iterum crucifigi. ei ait ad eum Petrus: Domine, iterum crucifigeris? Et dixit ad eum dominus: Etiam, iterum crucifigar. Petrus autem dixit: Domine, revertar et sequar te. Et his dictis dominus ascendit in caelum. Petrus autem prosecutus est eum multo intuitu atque dulcissimis lacrimis. et post haec rediens in se ipsum intellexit de sua dictum passione, quod in eo dominus esset passurus, qui patitur in electis misericordiae compassione et glorificationis celebritate.”

Peter interprets (“intellexit”) the vision to mean that Christ would be crucified once more through Peter’s own crucifixion. This act of interpretation is particularly important for understanding the uncertainty in Peter’s expression: He made a free choice to return to Rome based solely on this interpretation, thereby ensuring his own crucifixion.

Just before Jesus’ (first) crucifixion, Peter had been asked to make a similar decision between self-preservation or punishment – in fact, the exact wording “Domine, quo vadis?” makes an appearance in relation to this story. This parallelism demands our attention. At the Last Supper, the Gospels tell us that Peter declared that he is willing to be punished along with Jesus. Jesus tells Peter that he is not ready to follow him. The account in the Gospel of John portrays the story thus:3

dicit ei Simon Petrus “Domine quo vadis?” respondit Iesus “quo ego vado non potes me modo sequi, sequeris autem postea.” dicit ei Petrus “quare non possum sequi te modo animam meam pro te ponam.” respondit Iesus “animam tuam pro me ponis amen. amen dico tibi non cantabit gallus donec me ter neges.”

As per Jesus’ prophecy, Peter denies his relationship to Jesus on the night that Jesus was arrested – presumably for the sake of self-preservation.

Peter’s vision in the Acta Petri appears to be an inversion of his denial of Jesus in the Gospels. When Peter first asks Jesus whether he can follow him, Jesus dismisses him, declaring that he is not yet ready to do so, “sequeris autem postea.” In the Acta Petri, it is now “postea,” and so Jesus allows Peter to follow him. Peter had made the same decision to save himself right up until the vision occurred, but, seeing Jesus in the Via Appia, he changes his mind. This ethical inversion parallels the literal inversion of the cross. Caravaggio’s stroke of brilliance lies in how he conveys Peter (although already on the cross) still in the transition from the mindset that led him to deny Jesus to the mindset that made him follow Jesus. Caravaggio weighs down Peter’s physical inversion on the cross with the gravitas (shown in both the executioners’ duress and Peter’s anguish) of this transition as it is happening.