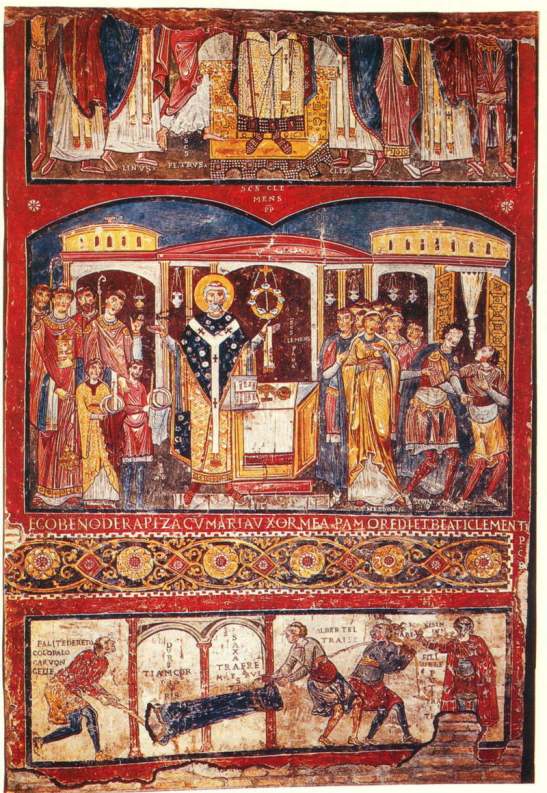

The Basilica di San Clemente is one of the most remarkable early Christian sites in Rome. The current church at street level dates from the 12th century, but it sits atop an earlier 4th century basilica built on the same spot. The earlier church, in turn, is above of a set of buildings from the first century AD which themselves contain the foundation of a Republican era house. The fresco shown above is in the 4th century basilica, but if you were to visit the excavations under S. Clemente today, you will find only a barely discernible faded image. The bright and vibrant image in this post is from a reproduction that the Irish monks in charge of the church commissioned when the fresco was first uncovered in the 19th century.1

The painting depicts a scene from legends concerning the life of St. Clement, which survive in a Greek hagiography of unknown date.2 In the first panel, a favorite (“φίλος”) of the emperor Trajan named Sisinnius has been consumed by jealousy and has followed his wife Theodora, who had recently converted to Christianity, to church.

[Θεοδῶραν] ὁ ἀνὴρ ζηλοτυπήσας, παγιδεῦσαι κατηγωνίζετο, πρὸς τὴν ἐκκλησίαν σπεύδουσαν. Καὶ δὴ εἰσερχομένης, ἐκεῖνο δι’ ἑτέρας εἰσόδου καταφθάσας, ἤρξατο πολυπραγμονεῖν· καὶ ἡνίκα παρὰ τοῦ ἁγίου Κλήμεντος εὐχὴ γέγονε, τοῦ λαοῦ εἰρηκότος τὸ Ἀμήν, ὁ Σισίννιος ἐν τούτῳ τυφλός τε καὶ κωφὸς ἀπετελέσθη, τοῦ μήτε ὁρᾷν, μήτε ἀκούειν δύνασθαι. Τότε οὖν λέγει τοῖς δούλοις αὐτοῦ· Λάβετέ με εἰς τὰς χεῖρας ὑμῶν, καὶ ἐξαγάγετε ἔξω, ὅτι οἱ ὀφθαλμοί μου τυφλοὶ γεγόνασι, καὶ αἱ ἀκοαί μου εἰς τοσοῦτον ἐκωφώθησαν, ὅτι οὐδὲν τὸ σύνολον ἀκούειν δύναμαι.3

The panel shows Pope Clement, exactly as the passage tells it, beginning the prayer (“εὐχή”). His arms are outstretched and held slightly up, a common position adopted for prayer in early Christian worship. Meanwhile Sisinnius, on the right, is being led out of the church by his servants after being struck blind and deaf.

The hagiography goes on to tell us that at Theodora’s request, Clement went to her home to cure her husband through prayer. When he gained his sight and hearing, however, Sisinnius took Clement for a magician and an adulterer and ordered his servants to seize him,

Καὶ ἰδὼν τὸν ἅγιον Κλήμεντα σὺν τῇ ἐαυτοῦ ἱστάμενον γυναικὶ, ἐξέστη τῇ διανοίᾳ λογιζόμενος τί ἄρα εἴη τοῦτο, καὶ ὑπονοῶν τοῦτο αὐτὸ γοητικαῖς τέχναις ἐμπεπαῖχθαι, ἤρξατο κράζειν τοῖς δούλοις αὐτοῦ· Κρατέσατε Κλήμεντα τὸν ἐπίσκοπον· διὰ γὰρ τοῦ εἰσελθεῖν πρὸς τὴν γυναῖκά μου, τῇ μαγικῇ αὐτοῦ τέχνῃ τὴν πήρωσίν μοι ἐπήγαγεν.4

However, again a miracle intervened and his servants tried to grab a stone column, thinking it was Clement,

Ἐκεῖνοι δὲ, οἷς ἐκέλευσε τὸν Κλήμεντα κατασφίγγειν τε καὶ σύρειν, αὐτοὶ τοὺς κειμένους στύλους δεσμοῦντες εἶλκον· ποτὲ μὲν ἔνδοθεν εἰς τὰ ἔξω, ποτὲ δὲ ἐκ τῶν ἔξω εἰς τὰ ἔσω· τοῦτο δὲ καὶ αὐτῷ τῷ Σισιννίῳ ἐδόκει, ὅτι περ τὸν ἅγιον Κλημεντα δεδεμένον εἰλκόν τε καὶ κατεῖχον. Πρὸς ὅν ὁ ἅγιος Κλήμης ἔφη· Ἡ σκληρότης τῆς καρδίας σου εἰς λίθους ἐτράπη· ἐπειδὴ γὰρ τοὺς λίθους δοξάζεις εἶναι θεοὺς, λίθους σύρειν κεκλήρωσαι.5

This scene is depicted on the bottom panel of the fresco. We see Sisinnius’s servants tugging at a column while Sisinnius himself, in full imperial outfit on the far right, urges them on. This panel is especially remarkable because the speech bubbles are some of the earliest known writing in Italian. On the left, the slave is shouting, “FALITE DERETO COLO PALO” (‘get behind with a pole’). On the far right, Sisinnius yells, “FILI DELE PUTE TRAITE” (‘Pull, you sons of whores’). Above the column, we see Clement’s response, written in Latin to underscore his more refined education and character: “DURITIAM CORDIS SAXA TRAERE MERUISTIS” (‘[because of] the hardness of your heart, you have deserved to pull stones’)

The legend of Sisinnius and Clement is a combination of elements from other stories concerning persecutions against Christians. The most obvious model is the story of Paul’s conversion in the book of Acts. Paul, who was then named Saul, set out for Damascus with the intention of arresting the Christians there and bringing them to Jerusalem. However, on the road, Jesus appeared to him as a burst of light and demanded that he cease his persecution.6 When Saul got up, Acts tells us “ἠγέρθη δὲ Σαῦλος ἀπὸ τῆς γῆς, ἀναφγμένων δὲ τῶν ὀφθαλμῶν αὐτοῦ οὐδὲν ἔβλεπεν· χειραγωγοῦντες δὲ αὐτὸν εἰσήγαγον εἰς Δαμασκόν. καὶ ἦν ἡμέρας τρεῖς μὴ βλέπων, καὶ οὐκ ἔφαγεν οὐδὲ ἔπιεν.”7 Like Sisinnius, Paul is struck blind to prevent his persecution and his servants have to lead him away by hand. Also like Sisinnius, Paul’s sight is only restored by the aid of a Christian. Acts tells us that a disciple named Ananias went to Paul and cured his blindness by laying hands on him.8

Unlike Paul, however, Sisinnius was not immediately converted by the restoration of his sight. Here the wording of Clement’s quote “Ἡ σκληρότης τῆς καρδίας σου εἰς λίθους ἐτράπη” (or “DURITIAM CORDIS” in the Latin inscription) reveals the source. This is undoubtedly a reference to God’s speeches to Moses in Exodus commanding him to confront the Pharaoh. Take for example this one, “ὁ δὲ ᾿Ααρὼν ὁ ἀδελφός σου λαλήσει πρὸς Φαραώ, ὥστε ἐξαποστεῖλαι τοὺς υἱοὺς ᾿Ισραὴλ ἐκ τῆς γῆς αὐτοῦ. ἐγὼ δὲ σκληρυνῶ τὴν καρδίαν Φαραὼ καὶ πληθυνῶ τὰ σημεῖά μου καὶ τὰ τέρατα ἐν γῇ Αἰγύπτῳ.”9 God uses the same terms for hardening Pharaoh’s heart (“σκληρυνῶ τὴν καρδίαν”) as Clement uses of Sisinnius (“Ἡ σκληρότης τῆς καρδίας”).

The legend of Clement and Sisinnius is representative of a kind of double rhetoric concerning converting pagans which is often found in early Christian texts. On the one hand, the example of Paul shows that conversions happen, and that even the most violent enemies of the church can become apostles. On the other hand, the example of Pharaoh shows that when conversions do not happen, the fault does not lie with lack of truth or righteousness on the part of the Christians. It lies with the hardness of their enemy’s hearts, a condition controlled only by God. Together they provide a powerful rhetorical tool to sustain a congregation through a period of persecution.

- The image source is here

- Tertullian and Irenaeus, our two earliest sources for information about Clement, mention nothing of the story.

- Migne Patrologia Graeca vo.2 co.620, “The husband, stricken with jealousy, set out to ensnare Theodora and he hurried to the church. And when he got there, having come in through another entrance, he began to spy. But as soon as Saint Clement made it to the prayer, and the congregation had said the ‘amen’, Sisinnius was in that moment struck both blind and deaf, so that he could neither see nor hear it. Then, therefore, he said to his slaves “Take me into your hands, and lead me out, because my eyes have become blind and my ears have become so deaf that I cannot hear anything whatsoever.” The full text is here

- Migne Patrologia Graeca vo.2 co.622, “And when he saw Saint Clement standing with his wife, he was struck with madness, thinking what this could be, and suspecting that this was brought about through magic arts, he began to shout to his slaves, “Sieze Clement the bishop, for in order to come see my wife he has struck me blind with his magic art.”

- Migne Patrologia Graeca vo.2 co.624, “But they, whom he ordered to bind and grab Clement, bound and dragged columns which were lying around, sometimes from outside to the inside, sometimes from the inside to the outside. But it seemed to Sisinnius that they had taken and held Saint Clement, having bound him. To him, Saint Clement said “The hardness of your heart has turned to toward stones, for since you believe that stones are gods, you have deserved to pull stones.”

- Acts 9.3-8. For the Greek text click here. For an English translation click here.

- Acts 9.8-9.

- Acts 9.10-19.

- Exodus 7.3-4. For the Greek text click here. For an English translation click here.