The Funeral of Fr. Reginald Foster, O.C.D.

A Personal Account of the Ceremonies at Holy Hill

When I am overburdened, I start coughing, and the night before Fr. Reginald Foster’s funeral I was coughing continually. As Fr. Foster’s biographer, I had gotten permission to attend his requiem mass and burial. Due to coronavirus restrictions, it would be a private ceremony. I was asked to keep the event in the strictest confidence: the Carmelites feared that many people would come, and come from far away. They were afraid of bringing COVID-19 into their monastery, especially with several elderly friars in their company. COVID, after all, was the very thing which killed Reginaldus in the end. And there were strict quarantine laws in the state of Wisconsin which they were obliged to comply with. The result was that I had no expectation of the consolation which funerals, as community rituals, afford. Many of my friends were friends of Reginaldus. But beside my wife, I did not know that any of them would be there. Among his students from Rome I feared I might be the only attendant. To carry, almost alone, the love of so many people, from all over the world, to a funeral seemed terribly lonely and sad to me. And I felt guilty about keeping the secret from some of them, whom I knew would drop everything they were doing and come if they knew and stand outside in the cold if no one let them in. I knew that because that was my plan as soon as I heard about the event. “If the Carmelite Provincial does not give me permission to come,” I told a friend, “I’ll stand outside and watch the cortege go by.” This is the kind of devotion we all have for Reginaldus.

And so when my wife Catherine and I pulled our car into the utterly empty parking lot at Holy Hill on Thursday, the 21st of January, I felt a wave of grief wash over me. We were told there would be viewing hours from 9 to 11 a.m.; it was 9:15. Not a car was in the lot. It was cold; lines of thin wind-driven snow streaked the lot. The wind that blows in January across Holy Hill, the highest point in Southeast Wisconsin, is something people from milder climes know nothing of. There is a viciousness to it, an uncaring constant gnaw, which drives gentler souls to warmer places.

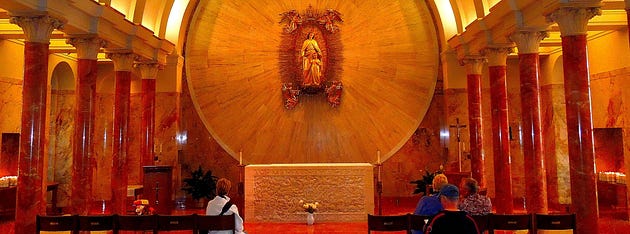

We made our way to the upper basilica. As soon as I entered I felt better. Holy Hill is a beautiful place; I could see why Reginaldus was happy here. And there was a buzz in the air: the place was alive. There were Carmelites milling about; many of them, in fact; the place had an almost medieval air about it, seeing so many monks in habits silently gliding from place to place. I could tell immediately this was a solemn occasion for them. It was their morning’s task, the burial of one of their brothers. And I could see a layman and woman seated in the front pew. It was easy to see that the man was related to Foster: thick build, round head with scattered thin hairs popping out of it. That must be his nephew Thomas. I was told he would be there. I made my way toward the front of the church when I turned to look into the Chapel of Our Lady, and what I saw almost made me gasp.

A coffin stood open by the altar, beneath the gaze of Our Lady of Holy Hill and her little child; and forgive the fact that I do not see well at a distance anymore, but what was in the coffin was so deathlike I thought for a moment it might just be a skeleton put in the coffin, as a kind of symbol. Reginaldus had died almost a month before, after all; a closed casket was a distinct possibility; maybe they would not put out the real body; perhaps they set out a mere memento mori. But as I approached I saw that no, these were his mortal remains: his face was yellow-gray, almost light brown; skull-colored, utterly deathlike, still the way no living flesh is still. The strong forehead and high cheekbones stood out; the head was raised on a little pillow, the chin sunken into the chest as only in corpses. His once-powerful hands were little more than bones and tendons. As I knelt before the coffin, I thought of a mass he had said in his monastery basement for his students. Those hands held the host just before the transubstantiation: Hoc est enim corpus meum, quod pro vobis tradetur. “For this is my body, which will be given up for you.” He was trying to live this, I thought at the time. He’s trying to give his body for us, every day, in his teaching, in his love for us. And now this was the consummation of it all. He had used up every little ounce of strength that was in that body to serve us. Here in death there seemed to be nothing left of it.

The funereal picture was completed by the fact that he was hooded, a brown monastic cowl over his head. The Carmelites had buried him in his habit! At first, I felt a bit of anger stir inside me: he had rebelled against ecclesiastical dress; the world defined him by his blue worksuit; they should have let him be in death as he was in life! But that feeling subsided. He had told us this is how he would be buried. “The last time I wore a habit was for my mother’s funeral,” he said. “The next time will be when the Carmelites put me in the ground.” He could have stopped this; could have left the Carmelites at any time. But he remained. He knew he would be buried as all Carmelites are buried. And seeing him there in that habit told me what I would be seeing: this day, this funeral, marked his return to the Carmelites, and his being welcomed back home as just another one of the brothers. And somehow, he wanted this. Even the fact that he would not be given a state funeral, and treated as a hero in death, as we his students wanted — one wrote, when told he was going to be buried at Holy Hill, “He should be buried in the PANTHEON” — this was as Reginald would have wanted it. A few years ago, when talking about funerals, he told me, “Bah, who cares about this STUFF… when I’m dead throw me in a ditch and DON’T put a name on it… what nonsense.” But in the last few years, back in Milwaukee, he knew that his death would be a return. A return to Wisconsin. A return to Holy Hill. A return to his family. A return to normalcy. And a return to the Carmelites.

But still in that chapel, there was also something indelibly Roman about it all, something Catholic, something Reginaldus himself would have loved. One favorite summer school story comes from a trip to Casamari, when all the students were yukking it up and having fun and then they entered the abbey to find a funeral taking place for one of the Cistercians. In a moment the mood passed from effervescent conviviality to solemn confrontation with death. He reveled in the moment, proud to be teaching his students, simply by bringing them into the world, something real. Rome too is like this: it is a city that does not shy away from death. To see a hooded friar in his coffin before a glorious altar of the Madonna and Child, while the living friars said their prayers and swished past: this was Rome, on top of this cold hill in Wisconsin.

After saying my prayers and thank-yous, I sat down in the chapel and pulled out my Lewis and Short. It had been with me the day I met Reginaldus twenty-five and a half years ago; now it was with us for his transitus. Sixty-five years ago he had fallen in love with the book after reading through the whole entry on amicitia. I wasn’t sure what to read. I could read the amicitia entry; it was appropriate, but I knew it already. I opened up to the word aeternus.

It says so much about him that I found so much in that entry consoling and appropriate. “Deus beatus et aeternus.” God, blessed and eternal. “Nihil quod ortum sit, aeternum esse potest.” Nothing which could have a beginning, can be eternal. This was an old joke between the two of us — the characteristic subjunctive. “There’s your Princeton,” he would always say to me. Then turning to everyone else, “They have a NEW JERSEY OBSESSION with the characteristic subjunctive down there.” (I still don’t know what a “New Jersey Obsession” is.) I kept reading. “Virorum bonorum mentes divinae mihi atque aeternae videntur esse.” The minds of good men seem to me to be divine and eternal. “Aeterna domus,” i.e. caelum. Heaven, our eternal home. “Donec veniret desiderium collium aeternorum.” Until the desire for the eternal hills should come. “Esp. of Rome, aeterna urbs, the Eternal City.” Yes indeed. “Vivet in aeternum.” He will live forever. “Tu es sacerdos in aeternum.” You are a priest, forever. So much glorious Latin. And it was like his spirit was there in each and every entry.

As I read, people were filing in, and inside the basilica it began to feel a bit like a wake. Conversations sprang up in various corners of the chapel: bursts of laughter, friends seeing old friends. All told there were about twenty Carmelites there, and about an equal number of laymen. Most of the laypeople were Foster’s nepotes, descendants via his brother and sister. Some old family friends. People who took care of him in the hospital. Some Milwaukee students. Patrick Owens (who was the one who remembered his words about being buried in his habit) and I represented his students from Rome — together with Milwaukee’s archbishop, Jerome Listecki.

The time came for the service to start. It was in English — which was disappointing, but it fit with the character of the day. The Carmelites were burying him, not as Reginaldus the Latin legend, but simply as one of their own. And, somehow, the service felt appropriate to him. I recognized the casket he was in (in an eminently suitable blue). It was the cheapest coffin you could get, cardboard covered with cloth, the kind that I, because I was born poor, was too embarrassed to choose for my mother and father when I saw it at the funeral home. We his students would have chiseled him a replica of St. Monica’s sarcophagus and covered it with quotations from Cicero and Leo Magnus, but when I saw what he had, I knew it was the right coffin for him. On the coffin the Carmelites placed his chalice and paten, a cross, a copy of the Carmelites’ Rule, and his Bible, a Latin Nova Vulgata taken from his room.

The readings were the customary ones: Job (“I know that my Redeemer Liveth”), Psalm 23 (“The Lord is my shepherd”), Romans (“no one lives for himself alone”), and John (“in my father’s house are many rooms”). The Romans passage is worth quoting at length, because it was relevant.

Nemo enim nostrum sibi vivit, et nemo sibi moritur. Sive enim vivemus, Domino vivimus: sive morimur, Domino morimur. Sive ergo vivimus, sive morimur, Domini sumus. In hoc enim Christus mortuus est, et resurrexit: ut et mortuorum et vivorum dominetur. Tu autem quid judicas fratrem tuum? aut tu quare spernis fratrem tuum? omnes enim stabimus ante tribunal Christi.

No one of us lives for himself, and no one dies for himself. For if we shall live, we live for the Lord, or if we die, we die for the Lord. Therefore we are the Lord’s, whether we live or die. For Christ died for this, and rose again: that he might have dominion over the living and the dead. So you — why do you judge your brother? Or why do you spurn your brother? We all will stand before the judgement-seat of Christ.

The Gospel was also relevant, but it was properly reflected, I believe in the homily by Fr. Michael Berry, the Washington Provincial of the Order of Discalced Carmelites.

The homily is well worth reading in full. It is, I think, one of the truest and deepest appreciations of Reginaldus ever to appear in print. Students might object that it is churchy; but after spending much time with him over the years, and researching his past life, I can attest that the Church was certainly the Alpha of his life, and in the end it proved the Omega too. Fr. Berry also went into the archives and retrieved several priceless documents about Reginaldus’s life. He had the recommendation letter his pastor at St. Anne’s parish (where he went to elementary school) wrote to the Carmelites, which concluded with one of the greatest whoppers in the history of recommendation letters: “He is a little more religious in his practices of devotion than boys ordinarily are. He often spends many hours a day in church in prayer. He is not eccentric, however.” That got some laughs, as you might imagine.

He had the letters Reginaldus, then known as Thomas, wrote to gain admission to the Carmelites. And he had an extraordinary 1966 letter of Reginald to the Washington Provincial, begging to be allowed to go to the Pontificium Institutum Altioris Latinitatis, rather than be forced to do a doctorate in theology, which his superiors in Rome wanted him to do: “If the superiors … decide on that, I will have to obediently satisfy this obligation first, before anything else that may be in view. What my one concern is at the present, my study, my interest, love, hope, ambition, my life in so many ways, for the glory of God, the good of the Church, and the honor of the Order, is in one word: LATIN.” Amazing. And Fr. Berry went on to discuss how Latin, to Reginaldus, meant,down deep, a Humanistic enterprise: “He reveled in leading his students to comprehend and to better appreciate, by various Latin texts they translated, what it means to be human. To be awed by it and to be humbled by it, to be humored by it and to be changed by it.” If you read that slowly, as Fr. Berry did, you will see just how much of Reggie’s whole teaching enterprise is contained in that one sentence.

Fr. Berry also went into some detail on the symbolism of his death on the Feast of the Nativity. Somehow so many of us found this fact consoling. And hearing that he used to spend his Christmases and Easters in Rome saying mass for the Carmelite sisters there — and to hear how they remembered him, as he most certainly remembered them — was beautiful.

After the sacrifice of the Mass was over, Archbishop Jerome Listecki rose to add some concluding comments. Listecki, a Midwestern son of a bus driver, had studied with Reginaldus in the late 70s and early 80s. He also did honor to Reginaldus with many of his comments, calling him a “Latin Einstein” and praising his life of poverty. “Amid the glories of Rome, he walked the streets like Saint Francis.”

As the ceremony came to a close, the Carmelites did as they do every day, and turned to the altar and sang the Salve Regina, modo Gregoriano. It was exquisitely beautiful and simple, and reminded me of all that time Reginaldus spent teaching us chant — blowing our mind with the revelation that many Gregorian chants shared the same meters as Sapphics and Alcaics and other ancient poetic forms. And then we heard the In Paradisum, and it was time for the tears.

In paradisum deducant te Angeli;

In tuo adventu suscipiant te martyres,

Et perducant te in civitatem sanctam Jerusalem.

Chorus angelorum te suscipiat,

Et cum Lazaro quondam paupere

Aeternam habeas requiem.

May the angels lead you into paradise; may the martyrs receive you at your coming, and lead you into the holy city Jerusalem. May the choir of angels lift you up, and with Lazarus, once a poor man, may you have eternal rest.

The body was brought by hearse down to the Carmelites’ burial-ground in a glade just below the hill. There the interment prayers were said, and in parting the Carmelites sang for him the Flos Carmeli, a beautiful Carmelite Marian hymn (translation here). The prayer cards printed for the funeral bore the same text:

Flos Carmeli,

vitis florigera,

splendor caeli,

virgo puerpera

singularis.

Mater mitis

sed viri nescia

Carmelitis

da privilegia

Stella Maris.

Radix Jesse

germinans flosculum

nos ad esse

tecum in saeculum

patiaris.

Inter spinas

quae crescis lilium

serva puras

mentes fragilium

tutelaris.

Armatura

fortis pugnantium

furunt bella

tende praesidium

scapularis.

Per incerta

prudens consilium

per adversa

iuge solatium

largiaris.

Mater dulcis

Carmeli domina,

plebem tuam

reple laetitia

qua bearis.

Paradisi

clavis et ianua,

fac nos duci

quo, Mater, gloria

coronaris. Amen.

They sang the whole thing, and they sang it beautifully, and I thought there could be no greater honor in his own eyes than to have everyone singing together. And I could imagine him asking what was the meaning of “iuge” was or what form “quo” was (“Be careful, friends!”). And then I saw the Carmelites walk back up the hill, through the woods, to their monastery. “We don’t say goodbye, friends,” Reginaldus always used to say, “we just go.” I followed at a distance, to spend some time in the church, looking over the Latin inscriptions and getting a better feel for the place. When I went outside again, this time with my children, we found the grave filled in, and a simple wooden cross planted in the earth. We placed some flowers on the grave — he always loved it when I brought him flowers — and went. But I thought, as I looked back on that spot in the woods, that we would be back.

John Byron Kuhner is editor of In Medias Res. He is currently writing a biography of Fr. Reginald Foster, for which he is gathering pictures, stories, testimonials, and dicta.

Sign up to receive email updates about new articles

Comment

Sign in with