What is Rome's Greatest Latin Inscription?

Metaphor Becomes Concrete Beneath Michelangelo’s Dome

[A version of this article first appeared in the February 2020 edition of Inside the Vatican magazine.]

Rome is replete with Latin inscriptions. They’re all over the churches, homes, fountains, obelisks, art, and museums. But what is the greatest of all Rome’s inscriptions? Which offers the most satisfaction, intellectual, artistic, or aesthetic?

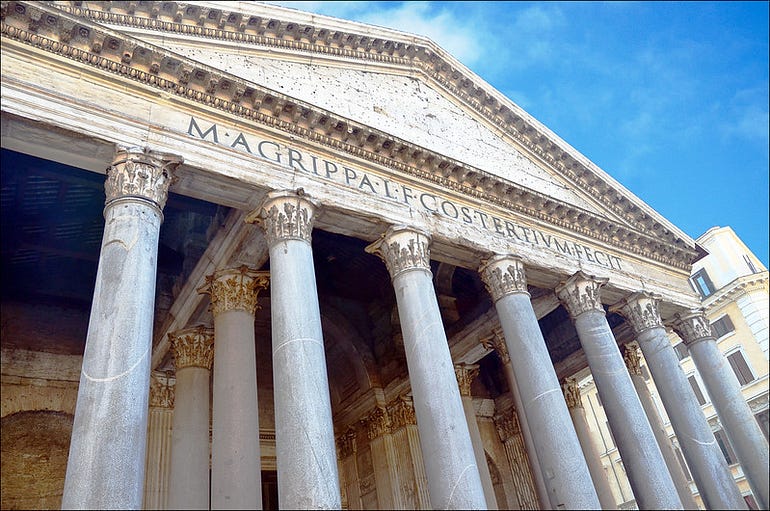

For many, the answer is Marcus Agrippa’s inscription on the Pantheon: M AGRIPPA L F COS TERTIUM FECIT. Its great big black letters fill up the entire piazza, and manage to be grand and overwhelming while also being austere and restrained. All it says is “Marcus Agrippa, son of Lucius, consul for the third time, made this.” But an entire world is called up by those few letters: that a man should elevate his own name, and his father’s; that political preferment — and especially to be chosen for Rome’s highest political office, the consulship — was the defining feature of excellence; and that creation — doing, making, facere in Latin — is the highest, greatest act of all, are all aspects of Roman culture on display in this short inscription. It’s probably the most complete evocation of Romanitas ever chiseled, and was apparently even recognized as such in antiquity. The inscription has been preserved, though the building it graced has not: a century and a half after Agrippa, Hadrian completely rebuilt the structure. But he transferred Agrippa’s inscription, which could not be improved upon, to the new building.

What other inscriptions in Rome can be placed with Agrippa’s? When you think about them, most of them seem tedious and verbose, or trite and unappealing, by comparison. But I think Rome boasts an inscription even greater than the Pantheon’s. It’s in St. Peter’s, adorning the inside of Michelangelo’s dome: TU ES PETRUS ET SUPER HANC PETRAM AEDIFICABO ECCLESIAM MEAM, ET TIBI DABO CLAVES REGNI CAELORUM. “You are Peter, and on this rock [“petram”] I will build my church, and to you I will give the keys of the kingdom of the heavens.” This is Jesus talking to Peter in Matthew 16, giving him a new name, “Peter” (“Rocky”). The Latin pun between Petrus and petra comes right from Greek, which in turn comes from Aramaic (Jesus apparently really called Simon “Cephas”). It’s a remarkable fact that the pun works fine in Greek, and then works in Latin as well because of Latin’s willingness to borrow foreign words. In this passage “Peter” becomes Simon’s new name as head of the universal church — his papal name, you might say. The future tense verbs, aedificabo and d dabo, are remarkable because they point to Christ’s church-building as not an activity Jesus was engaged in at the time, but a future activity — as if pointing to all later church history.

The best way to experience the inscription is to start with the Vatican’s remarkable “Scavi Tour,” which allows visitors (only a dozen at a time, which seems an appropriate number) to descend into the ancient cemetery upon which the basilica was built. You can walk on the ancient road, lined with ancient sepulchers. There is one tomb — right beneath the altar — which shows all the typical signs of importance: later burials crowd around it; ancient graffiti is scratched onto it (mentioning Peter); several altars were built into its side; and the human remains inside were wrapped in purple cloth edged with gold. An ancient little tabernacle, called an aedicula, marks the tomb, and the aedicula itself is enclosed in a marble altar from the age of Constantine. Directly above this tomb — which by tradition undisputed in antiquity has been known as the tomb of St. Peter — is the main altar of the basilica, the baldacchino of Bernini, and the dome of Michelangelo. From the purple cloth to the Constantinian altar to the dome, each generation has in its own way paid homage to the fisherman supposedly buried on this site. To complete your experience, you can climb the dome on foot, passing along a walkway on the inside of the dome just a few feet above the great TU ES PETRUS inscription. And so when you read the inscription, in the second person, as if spoken by the entire Body of Christ to its servant, you realize that it has all come true: an entire church has in fact been raised, with the bones of Peter as its foundation. The metaphor has become literal fact.

Now how Jesus may have meant the metaphor is a subject for dispute, although the dispute is often not of any inspiring intellectual quality. As is the norm, people treat the evidence as needed to produce the result they desire. People who venerate every line of the Bible might avoid these lines; or Biblical literalists might adopt a metaphorical reading here (“Peter” here is just a metaphor for “faith”). Others are sure they’ve got better information about what Jesus really said or meant. I’ve always found the certainty people have about these things a bit odd. During a freshman year course at Princeton University, I heard an English professor opine in class that “Jesus as everybody knows had never intended to start a church.” As a Catholic there was no way I was going to let this comment go unopposed, so I asked simply, “If you think Jesus never intended to start a church, how do you interpret those words that are in six-foot letters around the tomb of Peter, ‘You are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church’?”

My professor looked at me, paused for a moment, and said, “That’s a very good response to a longstanding and perhaps insufficiently examined opinion of mine.” He then somewhat incongruously resumed his lesson plan (we were doing a week on “the Bible as literature”), that despite the choosing of the Twelve, the sending out of the Seventy-Two, the institution of a Rite of Baptism, the request to reenact the Last Supper “in memory of me,” and the Great Commission (all of which I started pointing out), Jesus never intended to start a church (that was all Paul’s doing, you see). How moderns can gain knowledge like this I have no idea. It’s fine to question whether Jesus ever intended to start his own “gathering” (ecclesia, church); all we can say is that the earliest sources that quote Jesus quote him as intending to build one. It seems people must have something to be certain about; they replace one certitude with another. But my first solo trip to Rome, taken just after graduating from high school, had already wakened me to something which has always been more important to me: a sense of wonder at the depth of human commitment to this faith, extending through centuries and embracing every human type, inspired by the physical remains of that faith. It made me curious, so I would never be satisfied with a Religion 101 answer as to what it was “really” about. And one of the reasons why the experience was so intimate was that I knew Latin: when you climb to the top of the dome of St. Peter’s, and read that massive inscription word by word, walking around the whole dome, it affects you. You see how it has all literally been built on the foundation of Peter: you have an experience of church history as an imperfect but frequently deeply sincere attempt to honor and follow Christ the way that Jesus himself commended — by clinging to the rock of Peter. The inscription there guides your interpretation, and reading it as you stand there you experience the building as its many builders, Michelangelo preeminently, wanted you to experience it: as a stone-and-mortar embodiment of the words of Christ, incarnated by his followers in honor of the man he chose to be chief of his apostles. Whether you’re a believer or not, it’d be hard to find an inscription that offers its reader more than that.

John Byron Kuhner is the former president of The North American Institute for Living Latin Studies (SALVI) and editor of In Medias Res.

Sign up to receive email updates about new articles

Comment

Sign in with