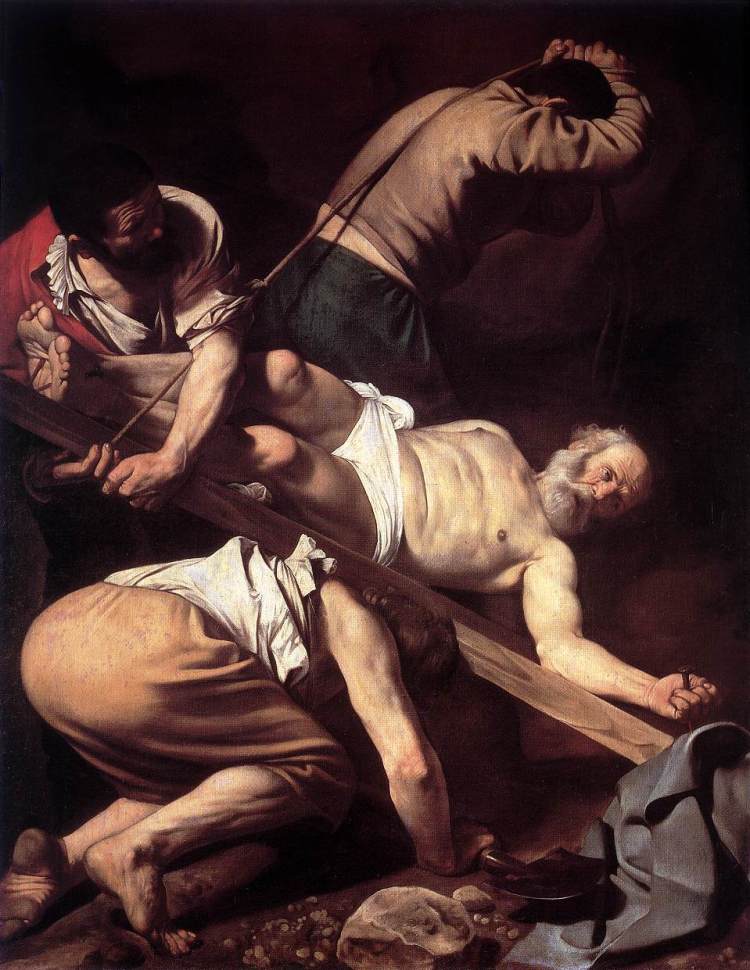

Just inside the unassuming Chiesa di Santa Maria del Popolo lie two, slightly obscured, masterpieces of the Baroque era. In fact, you might not even know they existed, were it not for the hordes of tourists twisting their necks to see them. Neither piece takes the central position over the altar in the Cerasi Chapel.1 As you look up to the left, you see the striking image of Saint Peter’s crucifixion portrayed by the Baroque painter, Caravaggio.

The painting’s immediate features are enough to stun any viewer. Caravaggio’s renowned use of chiaroscuro (the dramatic shift from light to dark) places Peter’s particularly bedraggled body and troubled expression in the spotlight, while dimming our view of his executioners’ faces. Caravaggio’s brutally naturalistic depiction of St. Peter marks a drastic departure from Michelangelo’s idealistic figures. And then we have the drama of the scene itself: A crucified man is being turned upside down. Caravaggio shows his figures in the midst of the action and deliberately places each gruesome, straining muscle in the foreground – including one man’s behind. Peter himself appears more like the working man than a saint. Perhaps most puzzling to the viewer is Peter’s emotional state. Is his a face of anguish, determination, or something else?