The fresco above, today on display in the National Archaeological Museum in Naples, shows the Amphitheater of Naples with scenes of street violence and mayhem.1 In this case we are quite lucky because this exact incident, a riot in 59 A.D. between the Pompeians and the residents of Nuceria, is described by the historian Tacitus:

Loci in Locis is an art and Classics blog that pairs artwork from sites in Rome with a thematically-linked Latin or Greek text. Posts aim to replicate on a small scale the context-based learning experience provided by Paideia’s Living Latin in Rome programs on a bimonthly basis. By marrying text, place, and image, we are able to form close and personal relationships with the classics in a way we might not be able to through text alone.

Loci in Locis is written and run by Paideia’s Rome Fellows. This year's Rome Fellows are: Tyler Dobbs, Gabriel Kuhl, Amanda Reeves, and Rebecca Williams. The blog is edited by Meaghan Carley, Senior Rome Fellow.

Little Elephant, Big Burden

December 07, 2015

There is a most curious artwork outside out of Santa Maria sopra Minerva that many visitors to Rome will have come across but few will have understood: the elephant obelisk by Gian Lorenzo Bernini. The question often asked--most naturally--is why on earth is an elephant under that obelisk? The answer, at least in part, can be found between the inscriptions on the plinth of the sculpture and the symbolic tradition of elephants.

The inscription facing away from the Church is the dedication by Pope Alexander VII:

VETEREM OBELISCUM

PALLADIS ÆGYPTIÆ MONVUMENTVM

E TELLVRE ERVTVM

ET IN MINERVAE OLIM

NVNC DEIPARAE GENITRICIS

FORO ERECTVM

DIVINAE SAPIENTIAE

ALEXANDER VII DEDICAVIT

ANNO SAL MDCLXVII.1

The Amphitheater of Pompeii Fresco

February 07, 2015

Sub idem tempus levi initio atrox caedes orta inter colonos Nucerinos Pompeianosque gladiatorio spectaculo, quod Livineius Regulus, quem motum senatu rettuli, edebat. Quippe oppidana lascivia in vicem incessentes probra, dein saxa, postremo ferrum sumpsere, validiore Pompeianorum plebe, apud quos spectaculum edebatur. Ergo deportati sunt in urbem multi e Nucerinis trunco per vulnera corpore ac plerique liberorum aut parentum mortes deflebant. Cuius rei iudicium princeps senatui, senatus consulibus permisit. Et rursus re ad patres relata, prohibiti publice in decem annos eius modi coetu Pompeiani collegiaque, quae contra leges instituerant, dissoluta; Livineius et qui alii seditionem conciverant exilio multati sunt.2

Ludovisi Gaul

January 16, 2015

The Ludovisi Gaul (also called “The Galatian Suicide”), situated in the center of a grand, largely empty salon in the Palazzo Altemps, is confrontational and dynamic. While the plunging sword and the fallen woman confront you first, the Gaul’s flung-back head compels you to circle the statue’s entirety. Regardless of context, witnessing a suicide in action is difficult precisely because of its inherent tension between action and passivity; it is the active decision to move into a state of utter inaction. The artist has rendered this tension explicitly by portraying both states: The limp form of the deceased woman embodies the passivity that comes with death and the strong movement of the soldier impresses the forcefulness of life. The Gaul’s fierce expression suggests that this man is no coward. How can we make sense of this clearly tragic scene?

Antoninus

December 28, 2014

The photo above shows the statue known as the Braschi Antinous, on display in the Musei Vaticani.1 The museum catalog gives the identification in this way:

In this statue, which dates from the years immediately following his death, Antinous is shown in a syncretic Dionysus-Osiris pose. On his head is a crown of leaves and ivy berries, and a diadem which at the top would originally have held a cobra (uraeus) or a lotus flower, but which the modern restorers have replaced with a sort of pine cone. The Dionysian attributes of the thyrsus and the mystical chest are also modern additions.2

Antinous himself is a figure shrouded in mystery and palace intrigue. We know from literary sources that he was a young man from Bithynia who had attracted the amorous attentions of the emperor Hadrian. Cassius Dio describes Antinous as a “παιδικὰ” (a “boy-toy”) of Hadrian, suggesting that in taking the lover, the emperor was trying to imitate models of traditional Greek pederasty.3 Antinous followed Hadrian on his tours of the provinces and died in Egypt. His death was the subject of controversy and the source of his lasting fame. There was a rumor that Antinous had been offered as a human sacrifice for the health of his lover and emperor. Cassius Dio gives us a succinct summary of the opposing stories of Antinous’s death:

ἐν τῇ Αἰγύπτῳ ἐτελεύτησεν, εἴτ᾽ οὖν ἐς τὸν Νεῖλον ἐκπεσών, ὡς Ἁδριανὸς γράφει, εἴτε καὶ ἱερουργηθείς, ὡς ἡ ἀλήθεια ἔχει.4

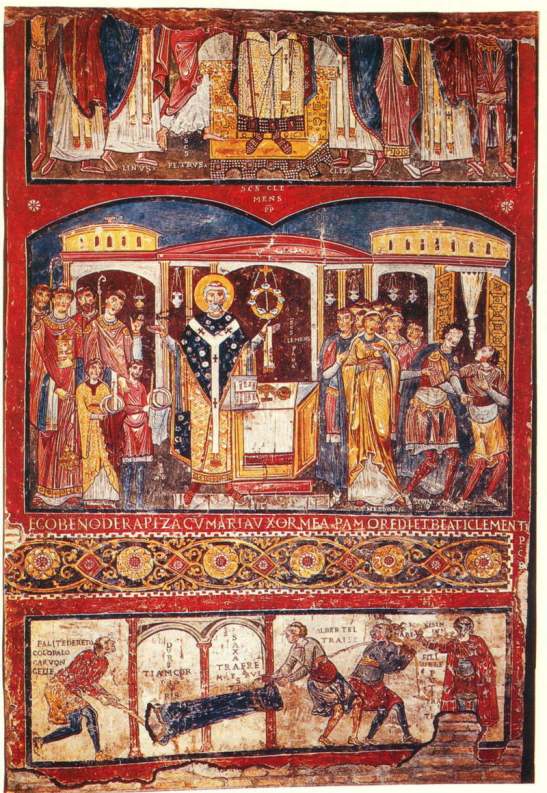

The Fresco of Sisinnius and St. Clement

November 23, 2014

The Basilica di San Clemente is one of the most remarkable early Christian sites in Rome. The current church at street level dates from the 12th century, but it sits atop an earlier 4th century basilica built on the same spot. The earlier church, in turn, is above of a set of buildings from the first century AD which themselves contain the foundation of a Republican era house. The fresco shown above is in the 4th century basilica, but if you were to visit the excavations under S. Clemente today, you will find only a barely discernible faded image. The bright and vibrant image in this post is from a reproduction that the Irish monks in charge of the church commissioned when the fresco was first uncovered in the 19th century.1

The painting depicts a scene from legends concerning the life of St. Clement, which survive in a Greek hagiography of unknown date.2 In the first panel, a favorite (“φίλος”) of the emperor Trajan named Sisinnius has been consumed by jealousy and has followed his wife Theodora, who had recently converted to Christianity, to church.

[Θεοδῶραν] ὁ ἀνὴρ ζηλοτυπήσας, παγιδεῦσαι κατηγωνίζετο, πρὸς τὴν ἐκκλησίαν σπεύδουσαν. Καὶ δὴ εἰσερχομένης, ἐκεῖνο δι’ ἑτέρας εἰσόδου καταφθάσας, ἤρξατο πολυπραγμονεῖν· καὶ ἡνίκα παρὰ τοῦ ἁγίου Κλήμεντος εὐχὴ γέγονε, τοῦ λαοῦ εἰρηκότος τὸ Ἀμήν, ὁ Σισίννιος ἐν τούτῳ τυφλός τε καὶ κωφὸς ἀπετελέσθη, τοῦ μήτε ὁρᾷν, μήτε ἀκούειν δύνασθαι. Τότε οὖν λέγει τοῖς δούλοις αὐτοῦ· Λάβετέ με εἰς τὰς χεῖρας ὑμῶν, καὶ ἐξαγάγετε ἔξω, ὅτι οἱ ὀφθαλμοί μου τυφλοὶ γεγόνασι, καὶ αἱ ἀκοαί μου εἰς τοσοῦτον ἐκωφώθησαν, ὅτι οὐδὲν τὸ σύνολον ἀκούειν δύναμαι.3