The Man Who Died To Leave a Tomb

The Curious Ozymandian Pyramid of Gaius Cestius

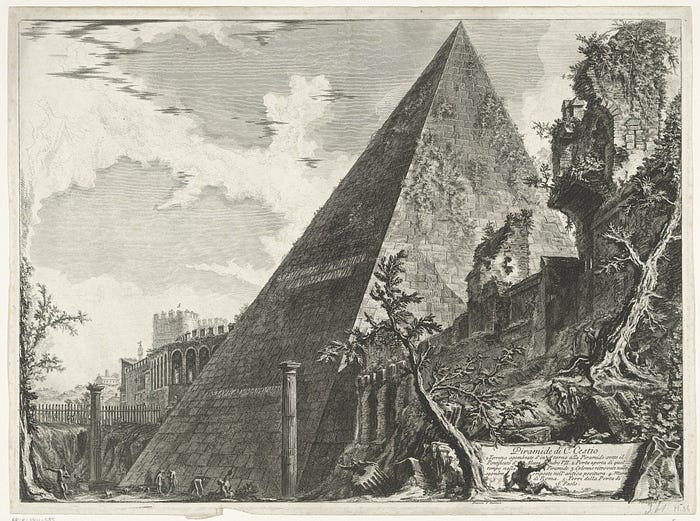

The Pyramid of Cestius by Piranesi. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The Pyramid of Cestius by Piranesi. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons..

Who, then, was Cestius,

And what is he to me? -

Amid thick thoughts and memories multitudinous

One thought alone brings he.

I can recall no word

Of anything he did;

For me he is a man who died and was interred

To leave a pyramid. — Thomas Hardy

It is easy to bemoan the lack of remnants, both textual and physical, surviving from Ancient Rome. Sometimes, what remains is reliant on the forces of human bias. Since not everything could be maintained, people only worked to preserve what they deemed worthwhile; our knowledge of history is formed by those books of Livy the ancient esteemed above others. Sometimes, what lasts is not the result of whim, but evidence of old mistakes and misunderstandings. The famous Marcus Aurelius statue currently in the Capitoline Museums stands only because the Christians believed that it depicted their favorite emperor, Constantine. But sometimes, nothing more than random Fortuna intervened. Such is the case in the Pyramid of Cestius, the gleaming marble structure that towers over the Protestant Cemetery in Rome.

Hardy’s first question is easily answered. The main source we have for Cestius is his epitaph. The text reads:

C. CESTIVS L.F. POB. EPVLO PR. TR.PL.

VII VIR EPVLONVM

OPVS APSOLVTUM EX TESTAMENTO DIEBVS CCCXXX

ARBITRATV

L. PONTI P.F. CLA. MELAE HEREDIS ET POTHI L

Gaius Cestius, son of Lucius, of the gens Pobilia, member of the College of Epulones, praetor, tribune of the plebs, septemvir of the Epulones. The work was completed, in accordance with the will, in 330 days, by the decision of the heir Lucius Pontus Mela, son of Publius of the gens Claudia, and Pothus, freedman. [Translation from Amanda Claridge’s “Rome: An Oxford Archaeological Guide”]

But the inscription decorating the side of the pyramid does not help us answer Hardy’s second, more difficult question. Besides the dedication to Cestius, including his titles and the attribution of the tomb’s creation to his heirs, the epitaph only mentions how long it took to build. This addition may be a comparison to the Egyptian pyramids and the impressive speed at which Romans could build pyramids. But all in all, this epitaph is decidedly bland. Where is the elegy bemoaning the loss of such a great man? Where is the hexameter celebrating his great deeds as praetor? The sparse inscription contributes to the mystique of Cestius. This man had enough of an ego to have a pyramid built for his bones, and yet could barely bring himself to put his name to it.

The inscription was so little regarded that even Petrarch mistakenly calls this pyramid the tomb of Remus in a letter. Unfortunately, this letter is lost, known only to us from Poggio’s acid remark in De Varietate Fortunae. He amusingly states:

Quo magis miror, integro adhuc epigrammate, doctissimum virum Franciscum Petrarcham in quadam sua epistola scribere, id esse sepulcrum Remi: credo, secutum vulgi opinionem, non magni fecisse epigramma perquirere, fruticetis contectum, in quo legendo, qui postmodum secuti sunt, minore cum doctrina maiorem diligentiam praebuerunt.

By which the more I wonder about the inscription, that a most learned man, Francis Petrarch, wrote in a certain one of his letters, that it [the Pyramid of Cestius] is the tomb of Remus: I believe he, following the opinion of the common, had not considered it important to look for an inscription, covered up by plants, in the reading of which, those who followed after, have shown less learning, but more diligence. [Translation mine.]

While acknowledging Petrarch’s learnedness, Poggio also critiques his carelessness in missing a relatively clear inscription on the side of the pyramid. The inscription notwithstanding, Petrarch’s faulty assumption is understandable considering there was only one other pyramid-tomb in Rome, which was called the Tomb of Romulus. His mistake reinforces the fact that without the carved testament to Cestius’ ownership, not even a man as erudite as Petrarch would think to ascribe such a grand tomb to anyone less than one of the legendary founders of Rome.

Yet scholars actually believe that Cestius’ tomb was built long after the founding of Rome — around 12 years before the birth of Christ — and it has stylistic markers that identify it as a product of its era. Romans at the time, having recently subdued Egypt, became obsessed with all things Egyptian, as is evidenced by the import of giant obelisks to decorate sites like the Circus Maximus. However, while this tomb is modeled off of the Egyptian pyramids, some license was taken with the design. The inside contains only a single frescoed burial chamber, and the sides are more steeply sloped than the original pyramids of the Old Kingdom Pharaohs. Perhaps Cestius was showing off how Roman engineering could use concrete to accomplish architectural feats which even the great Imhotep could not. Or perhaps he modeled it off of the later and more southern Kushite pyramids, which are steeper than their northern counterparts. The land of Kush was at the furthest point of Rome’s reach, so Cestius may have been showing off his extensive knowledge of the world. Because we know so little of Cestius and his life, we can’t be sure what the motives behind the design of this structure are.

This contrast between the relative anonymity of Cestius and the permanence of his pyramid presents, for me, an opportunity for intense reflection, and allows the monument to function as a powerful memento mori. If a man with the power and resources to leave such a permanent physical legacy is so little understood, I wonder how many identities and memories have been lost to oblivion. A comparison to Ozymandias seems apt here, especially given the tomb’s modern setting. Without a clear picture of the man, the tomb comes to represent the multitude of forgotten souls. As pessimistic as is the thought that most everyone will be forgotten someday, it gives me hope that although individuals are transient, the legacy of humanity lives on. Almost as if they felt this sentiment just as keenly, Romans years later incorporated the tomb into their Aurelian walls as a bastion to save building materials and time. Now, it literally as well as symbolically protects the memories of the dead, the living, and Rome itself.

Mitchell Towne works as a full-time Latin teacher, swim coach, and resident dorm faculty at Blair Academy. He served as Classics Tours Manager for Paideia from 2017–2019 during which time he led classical tours around Italy, Greece, and Sicily and administered the Living Latin in Rome High School and Living Greek in Greece High School programs. Earlier he was a Paideia Rome fellow from 2016–2017. An alumnus of Paideia’s Living Greek in Greece and Living Latin in Paris programs, he is a 2016 graduate of Williams College with a bachelor’s degree in Classics. He enjoys swimming and is currently learning to play the bouzouki.

Sign up to receive email updates about new articles

Comment

Sign in with