Elevator Latin

For Today’s Diversion, Try Something Both Classical and Uplifting

The view from Bergamo’s Civic Tower — just an elevator ride away

The view from Bergamo’s Civic Tower — just an elevator ride awayThe elevator inscription in the Vatican is legendary among Latinists. It used to be a rite of passage, a cool and customary treat, to go see it. Reggie Foster would take groups over the years, and he’d show it off with obvious irony and pride.

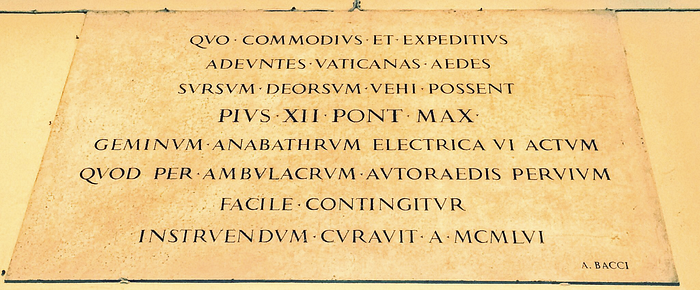

There was also, of course, the frisson of access you felt in getting to see it. The inscription’s mounted in an inner courtyard of the Vatican, and you can’t just walk in off the street — you needed permission to get in there. Here’s a picture I took back in summer 2016, the last time I was there:

Every time I saw it, this inscription led to giggles and flushed faces, because it’s clearly not the world’s easiest thing to decipher! Even superb Latinists would grope about trying to construe it at sight, and hilarious mistakes abounded. Here’s what it means:

IN ORDER THAT THOSE VISITING THE VATICAN BUILDINGS

MIGHT BE ABLE TO GET UP AND DOWN MORE CONVENIENTLY AND EFFICIENTLY,

POPE PIUS XII

HAD A DOUBLE ELECTRIC-POWERED ELEVATOR INSTALLED

WHICH IS EASILY REACHED BY A CAR-ACCESSIBLE WALKWAY.

— 1956 —

Even if you don’t stumble over that first quo (= ut, because of the comparatives commodius and expeditius), as many did, it takes serious brains and multiple tries to puzzle out that sixth line — the one about being “accessible to autoraedae.”

Some people think that must mean “wheelchair accessible.” But usually an autoraeda is a car, so it probably just means you can drive up to the elevator (hence in Italian, I gather, a passo carrabile). Wheelchair accessibility may be implicit, but it isn’t what the stone says.

It’s a strange thing, isn’t it? A normal person would be impressed with the elevator itself. That’s the gravity-defying, genius contraption that makes life better, makes getting around commodius and expeditius.

Latinists can be different. Most of us ignore the machine and gawk at the writing instead. It seems weird, crazy, impossible that anyone could describe an elevator in a language that died out thousands of years ago.

Until recently, I thought that was the only Latin elevator inscription around — a unicorn, a collectible.

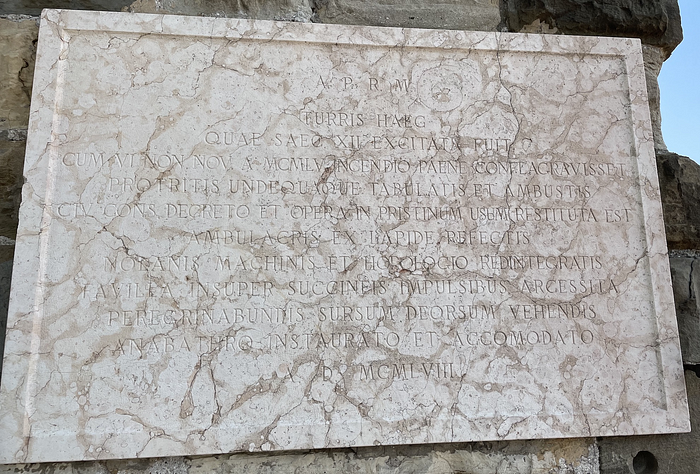

Not so. As I recently found to my delight, if you go to the top of the central tower in the upper city of Bergamo — an hour’s train ride from Milan, if that, and well worth it — you’ll see a plaque that looks like this off to the right.

The Bergamo Latin elevator inscription

The Bergamo Latin elevator inscriptionNo special access needed to see this one. The Latin’s a lot easier, too, and given the date — 1958 instead of 1956 — it’s a fair guess that it’s indebted to the Vatican inscription. It’s also very cool. Here’s a transcription:

A.P.R.M.

TURRIS HAEC

QUAE SAEC. XII EXCITATA FUIT

CUM VI NON. NOV. A MCMLV INCENDIO PAENE CONFLAGRAVISSET

PROTRITIS UNDEQUAQUE TABULATIS ET AMBUSTIS

CIV. CONS. DECRETO ET OPERA IN PRISTINUM USUM RESTITUTA EST

AMBULACRIS EX LAPIDE REFECTIS

NOLANIS MACHINIS ET HOROLOGIO REDINTEGRATIS

FAVILLA INSUPER SUCCINEIS IMPULSIBUS ARCESSITA

PEREGRINABUNDIS SURSUM DEORSUM VEHENDIS

ANABATHRO INSTAURATO ET ACCOMODATO

A.D. MCMLVIII

Now, the Latin may be easier, but that doesn’t mean it’s totally obvious. It took me a while to discover that A.P.R.M. stands for Ad Perpetuam Rei Memoriam. The date “VI Non. Nov.” is really weird, too, but it doesn’t seem any better to interpret VI as vi (ablative of vis, violence). Here’s the best I can do with it:

FOR A PERMANENT RECORD OF THE MATTER

AFTER THIS TOWER,

WHICH WAS ERECTED IN THE 12TH CENTURY,

ALMOST BURNED DOWN IN THE FIRE OF NOVEMBER 2 [?], 1955,

FLOORBOARDS ALL OVER THE PLACE BEING WORN OUT AND SCORCHED,

IT WAS RESTORED TO ITS ORIGINAL USE BY A DECREE AND THE EFFORT OF THE CITY COUNCIL,

THE WALKWAYS HAVING BEEN REBUILT FROM STONE,

THE BELL MACHINES AND CLOCK HAVING BEEN RECONSTRUCTED,

BY MEANS, MOREOVER, OF SPARKS GENERATED BY ELECTRIC SHOCKS,

AN ELEVATOR FOR CARRYING TOURISTS UP AND DOWN

HAVING BEEN FITTED OUT AND INTRODUCED.

— 1958 —

The line that obviously attracts interest is the ninth, favilla insuper succineis impulsibus arcessita. If I understand it, the inscription is saying they upgraded the bells and clocks to run on electrical instead of human power. If so, the author of this inscription seems to have rejected the Vatican’s word electrica and preferred suc(c)ineus, a word that properly means “amber” and that can occasionally refer to electricity (electricity comes from the Greek word for “amber,” by the way, electron. Amber, if you rub it, is a good source of electrons). In that case, favilla, which can mean “glowing embers” in addition to ashes, seems to be a word they’ve chosen for power (“embers having been sparked by electrical impulses”).

By the way, the inscription shows that the Civic Tower’s own information isn’t quite right. A placard near the ticket counter tells tourists the elevator was installed in 1960.

Oops.

Here’s a lingering question: Why exactly do Latinists call an elevator an anabathrum? It’s not the most obvious word to use, since it only shows up once, in a satire of Juvenal, and there it seems to mean “bleachers” or a “raised seat.”

I have a reasonably clear memory of Reggie crediting the word to Cardinal Antonio Bacci, the Latinist who vainly signed his name at the bottom right of the Vatican inscription.

But memory’s a tricky thing. I don’t trust it for something like this, and in digging around I found a couple fascinating things.

First, it appears the famous Vatican inscription known to me actually replaced an older one — replaced both an older inscription and an older elevator. John Kuhner tells me that according to a book of Bacci’s inscriptions, the following plaque used to hang in the “Aula Damasiana,” i.e. the same San Damaso courtyard:

PIVS XI PONT MAX

IN LOCVM VETERIS ANABATHRI

LENTO AQVAE MOLIMINE ACTI

HAEC GEMINA SCANSORIA PEGMATA

ELECTRIDE AGENDA SVFFECIT

OMNIBVSQVE IN ADSCENSVM IN DESCENSVM

PATERE IVSSIT

ANNO A REP SAL MDCCCCXXXII

That is,

POPE PIUS XI

HAD THE SLOW OLD ELEVATOR,

WHICH WAS HYDRAULIC POWERED,

REPLACED WITH THIS DOUBLE ELEVATOR,

WHICH IS ELECTRIC POWERED,

AND MADE IT AVAILABLE TO EVERYONE

FOR GOING UP AND DOWN.

— 1932 —

But that’s not all. I also discovered there is or was an even older elevator inscription in the Vatican, going all the way back to 1910! It reads:

EX AUCTORITATE PII X PONT. MAX.

AUSPICE MARIANO RAMPOLLA CARD. ARCHIEP.

JOSEPHO DE BISOGNO, CUR. OP. VAT.

ELECTRICUM ANABATHRUM

POSITUM

ANNO MDCCCX

That is,

BY THE AUTHORITY OF POPE PIUS X,

BY THE LEADERSHIP OF MARIANO RAMPOLLA, CARDINAL, ARCHBISHOP

AND GIUSEPPE DE BISOGNO, ADMINISTRATOR OF VATICAN WORKS

AN ELECTRIC ANABATHRUM

WAS PUT IN.

— 1910 —

Apparently, this inscription is located somewhere next to the elevator you take to get to the top of the cupola in St. Peter’s. The source I’m quoting it from attributes it to Petrus Angelinius (1847–1911), the Italian Latinist who once translated a book titled Anthea sive fabula “Eamus ad ipsum.” If anyone deserves credit for coining our word for an electric elevator, then, it’s surely him.

What’s more, the beauty of this earlier inscription is that it lets us understand how the word anabathrum came to be used for an elevator — especially since in 1932, as we saw above, Bacci had also used the seemingly more-suitable word pegmata for it.

The key is realizing that by 1910, the word anabathrum was was already in sporadic use in church Latin for a “pulpit.” And when you see what a pulpit looks like in any reasonably impressive European church, the metaphor clicks right into place. Imagine that wooden beauty slowly rising up the column it’s mounted on, and it all makes sense.

In searching for a good word for the elevator, Angelinius decided to call the elevator an “electric pulpit.”

Apparently wanting to improve on the looseness, Bacci tweaked that to a “pulpit driven by electric force” (electrica vi actum).

By the way, it seems the cupola elevator and inscription jolted the Muses a bit when they first made headlines, too. An American wit named Tudor Jenks (1857–1922) immediately penned a ditty to honor both, a ditty that Life magazine saw fit to print. It’s dated March 16, 1910, and it’s well worth reprinting here:

THAT BLESSED ELEVATOR

An electric elevator carrying ten persons has been installed in the stairway leading to the cupola in St Peter’s. An appropriate Latin inscription in which the elevator is termed “Electricum anabathrum” is placed at the entrance. The lift will be solemnly blessed and inaugurated by Cardinal Rampolla next Saturday.

WHY is the forum crowded? What means this stir in Rome?

’Tis Science — modern Science has seized St Peter’s dome!

“Anathema maranatha” were once the words of power,

But “anabathrum electricum” controls the present hour.

From fixed and ancient standards the Romans seem to drift:

They seek no longer “moral” but “electrical” uplift;

That something so new-fangled should in this age be bought

But goes to show the tendency to currents of new thought.

And though it saves a lot of steps, and many minutes, too,

No longer can we go to Rome to do as Romans do;

If Julius Caesar used a lift, the fact is nowhere stated —

Though Horace and his genial friends were often “elevated.”

“Electricum!” A word to make Quintilian gasp and stare —

(For stairs still were in his old day, though now they’re rather rare).

These lines are meant to note a fact, not for the sake of “knocking,”

But — as a bit of current news — isn’t it rather shocking?

Not too shabby for a little fun!

By the way, does anyone have a picture of that 1910 Vatican elevator inscription? If so, please send on and we’ll add it here.

Mike Fontaine is Professor of Classics at Cornell University.

Sign up to receive email updates about new articles

Comment

Sign in with