Flights of Fancy

Anthony Doerr’s Latest Novel “Cloud Cuckoo Land” Takes Us From Aristophanes to the Siege of Constantinople to Outer Space — But Does It Hold Together?

Anthony Doerr’s previous novel, All the Light You Cannot See, is a masterpiece. His latest novel, Cloud Cuckoo Land, is not. I worry that Aristophanes had something to do with that.

Readers of In Medias Res will recall that “Cloud Cuckoo Land” (Νεφελοκοκκυγία) is the fictionalized world that Pisthetaerus and Euelpides imagine in Aristophanes’ The Birds. The two protagonists envy birds and they try to imagine a new republic, Cloud Cuckoo Land, where they can join the birds and free themselves of the gods. As with all of Aristophanes, one is never sure where the comedy begins and the satire ends, whether they are coterminous, and how literally we ought to take the many and various puns. We know we should laugh — and we do — but we’re slightly afraid the joke is on us. (I wonder if the Athenian juries judging his plays felt the same way. And I wonder if they didn’t award him first prize for just that reason.) The ambiguity is part of the fun, of course, and the irony Aristophanes employs shows he’s closer to Socrates than he — or we — would like to admit. Perhaps Socrates and Aristophanes hope to teach us that irony keeps us just off kilter enough to approach the truth. They might be teaching us that imaging utopia helps us live in the world we inhabit.

Utopias and dystopias hang over Doerr’s novel, but instead of an ambiguity that prods the reader to think (as with Aristophanes), the reader is left with the confusion that comes from an unruly novel whose ends don’t tie together. We can only entertain utopian and dystopian models that are fully formed.

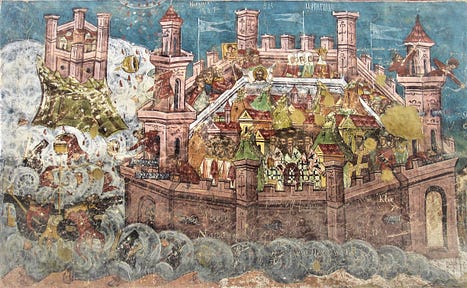

These utopias and dystopias focus on three story lines. The first is set in Constantinople in 1451, just before the siege of the city. In this story line we meet Anna, a Christian girl inside the city and Omeir, a Muslim boy who is conscripted to help storm it. The second story line takes place in mid to late 20th- and early 21st-century Idaho. Here we meet Zeno, who served in the Korean war, fell in love with a British soldier Rex, returned to Idaho to work in the public works department, learned ancient Greek, then worked with local students to stage a newly-discovered ancient Greek play, “Cloud Cuckoo Land” by a certain Antonius Diogenes that he translated. Finally, the third story line takes place in the distant (?) future in Mission Year 65 aboard the Argos, a space ship that will take human beings to a new, more inhabitable planet. Aboard the Argos, we meet Constance, a young girl captivated by learning, but unsure of her role in this mission.

Classical allusions fill the novel. I’ve already noted the characters Zeno and Constance, the ship Argos, and learning classical Greek. At its best (and Doerr says this in the acknowledgements), Cloud Cuckoo Land is a love letter to reading and a panegyric to the way texts bridge ages and places. Nausicaa captivates Anna and Constance. “Cloud Cuckoo Land,” the play, was saved by Anna before the siege, and Zeno’s translation and production brings children of his Idaho town together. Constance learns of the play on the Argos’s computer system.

But … Cloud Cuckoo Land falls short as a novel because ultimately novels rest on character and plot and allow ideas to flow from the narrative and the plot. All the Light We Cannot See, for example, explored nationalism, parenthood, war, friendship, forgiveness, and sound through Werner the German boy who loved engineering and was conscripted into Hitler’s army and Marie, the blind French girl who escaped Paris with her father as the Nazis invaded. Each character in the novel was necessary. Every story line played a role in the overall narrative. Readers came to care about the lessons their lives taught because readers cared about them.

Doerr paints sympathetic portraits of Anna, Zeno, and Constance, but the pictures stand by themselves. There is no thread that ties the story line together. The manuscript that escapes Constantinople and ends up in Idaho and beyond is a forced conceit. How is the reader meant to understand the allusion to Aristophanes? Are the classical allusions little more than window dressing? Are there parallels between the relationships of Anna and Omeir and Zeno and Rex? Is the violence portrayed salvific, tragic, senseless? In his pursuit of a big idea about the value of reading, Doerr loses the reader.

There is a good novel in Cloud Cuckoo Land, and it focuses on the story of Zeno. This story explores how he served his country, how his love for a man remained forbidden, how his love for Greek connected him with Rex and with his community, how his life was cut short. Seymour, a high school student whose story line is part of Zeno’s, has his own pathos, but in such a sprawling novel, it remains unclear how his story fits into the broader story of Constantinople and the Argos mission. If Cloud Cuckoo Land had focused on Zeno and Seymour — and nodded to the story’s manuscript history — the novel would have been tighter and its pace stronger.

When Zeno begins to translate “Cloud Cuckoo Land,” he remembers Rex’s love of Greek comedy and impossible journeys. He doesn’t recall (perhaps he doesn’t know?) Aristophanes’s fantastical world. (The novel’s epigraph comes from The Birds, but we don’t hear from the play again.) Doerr’s novel promises discussion of big themes, the kinds of themes that draw in lovers of classical literature. But the execution of the novel leaves the reader wondering if Aristophanes was right after all and that those big ideas ought to be considered as nothing more than a flight of fancy fit for birds.

[Cloud Cuckoo Land by Anthony Doerr was published by Scribner in 2021, and is available on Biblio here.]

Scott D. Moringiello is an associate professor of Catholic Studies at DePaul University in Chicago. He is the author of The Rhetoric of Faith: Irenaeus and the Structure of the Adversus Haereses.

Sign up to receive email updates about new articles

Comment

Sign in with