Rediscovering STEM's Latin Roots

A Review of Epstein and Spivak’s “The Latin of Science”

Marcelo Epstein and Ruth Spivak (eds.), The Latin of Science. Mundelein, IL:

Bolchazy-Carducci, 2019. 395 pp., $29.

Imagine you are in Latin class and your teacher hands you a text containing the following sentence, leaving it to you to guess who the author is:

Mutationem motus proportionalem esse vi motrici impressae, et fieri secundum lineam rectam qua vis illa imprimitur.

Most of the vocabulary is rather intuitive (lots of English derivatives!), and you might find the syntactic structure fairly straightforward — even though, at first glance, you might have a harder time figuring out who could possibly have written this bit of Latin. You will probably understand its meaning more or less as follows:

I say that the change of motion is proportional to the motive force impressed, and occurs in the direction of the straight line along which that force is impressed.

Your teacher then tells you that, in the author’s time, the Latin term motus does not only refer to “motion” in general, but can be used specifically to denote the “quantity of motion” or mechanical momentum, which is mass times velocity. You may now recall that, in a constant-mass system, the rate of change of an object’s momentum can be described just as well in terms of the object’s acceleration.

So, based on what the mysterious Latin author is saying, it logically follows that the force acting on a body is directly proportional to the body’s acceleration: more precisely, the force impressed is equal to the mass of the object times its acceleration. “Wait a second,” you might exclaim at this point, “this is Newton’s second law of motion!” And that is, in fact, the most widespread form in which the second law is now stated:

Quite strikingly, the formula which you have likely seen before (perhaps in a physics class) is ultimately a mathematical way of rephrasing Sir Isaac’s original Latin sentence. Newton’s second law is but one among many examples of just how often we overlook the fact that largely familiar, commonly taught propositions of modern science were first uttered, printed, formulated and disseminated in Latin.

Indeed, Latin was for centuries the universal lingua franca of science in western Europe, and as such it remained a living language of communication (at least among the educated strata of society) long after it had ceased to be spoken as a native language. In an important sense, science kept Latin alive — and vice versa.

Yet, for a long time, there was no handy resource that scholars and educators could use to introduce themselves and their students to the original Latin texts of the European scientific tradition. Until now. Marcelo Epstein and Ruth Spivak’s anthology, The Latin of Science, fills a major gap in the academic literature by offering precisely such a resource at an affordable price.

Who is this book for? The idea originated in a yearlong course offered by the Classics department at the University of Calgary and aimed primarily at science and engineering majors, alongside other non-Classics students.

The volume’s asserted goal is thus to expose non-classicists in general, and STEM students in particular, to the vast treasure trove of scientific works written in Latin over the past two millennia, and to bring users to a reasonable level of reading fluency in the target language — partly leveraging the well-known dynamics whereby familiar content facilitates comprehension and language acquisition. Classicists with an interest in the history of science from antiquity to the modern age will also find Spivak and Epstein’s volume very stimulating.

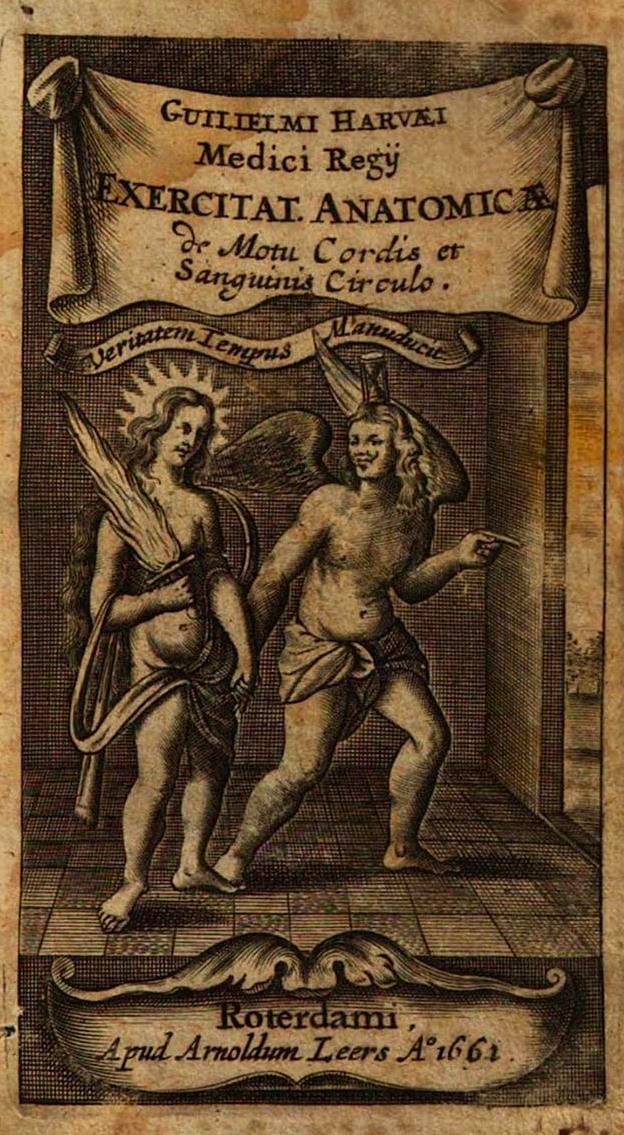

After a concise Introduction, the bulk of the book presents a wide array of selected Latin texts (of varying length) by seventeen scientific authors, grouped into eight genres: General Knowledge, Architecture & Engineering, Medicine, Mathematics, Astronomy & Rational Mechanics, Optics, Economics, and Chemistry. Each Latin excerpt is accompanied by short notes to the text, while each author is introduced by a few paragraphs providing some biographical and historical context.

As with every sourcebook of this kind, selecting a limited number of passages that are both accessible and representative of the subject-matter is a virtually insurmountable challenge. Spivak and Epstein tackle it as well as anyone could hope: alongside such obligatory (and predictable) choices as Seneca, Pliny the Elder, Leibniz, and Newton himself, the reader will also find hidden gems such as Cetius Faventinus’ architectural treatise, Andreas Libavius’ Alchemy, and a couple of medieval Latin translations of Euclid’s Elements (though, for instance, major medical authors like Celsus and Linacre are mysteriously left out).

Of particular interest are the Latin versions of Hebrew- and Arabic-speaking authors like Maimonides and Alhazen, whose work played a fundamental role in the cross-cultural development of medieval science. In this regard, selections of e.g. Domingo Gonzalez’ Latin translations (from Ibn Sina) and Gerard of Cremona’s (from Ptolemy, via Arabic versions) could have been valuable additions.

Spivak and Epstein’s presentation of the sources is commendable, particularly thanks to the generous amount of illustrations and facsimiles of early printed editions provided in the book (the publisher has also made them available online). The editors’ explanatory notes are generally useful, especially when they unravel relatively uncommon syntactic constructions or otherwise facilitate the comprehension of complex, heavily technical argumentations.

Specialized vocabulary is often glossed in the commentary, but students are encouraged to assimilate Latin roots and work out the meanings of new words based on derivation. After all, one of the most rewarding aspects of reading scientific Latin is the familiar ring of much of its terminology. Most non-classicists and STEM students will have no difficulty guessing the meaning of words like optica, machina, circumferentia and the like, even without previous exposure to Latin.

Occasional errors and infelicities do not detract from the overall quality of the commentary (pp. 22–23: the transmitted monster a potesaretes should have been emended in the text with a note, rather than left standing then glossed in the commentary; p. 180: the frontispice reads Thuringopoloni, not Thuringolopoli; p. 219: vaenire is an alternative form of veneo, not venio).

At the same time, the Appendices (especially Appendix II) are somewhat disappointing. Instead of embarking on the Sisyphean task of providing beginners with a “Compendium of Latin Grammar” in a mere forty pages (a task which could readily be outsourced to countless existing books), it would have been more helpful — and intriguing — to focus on the linguistic peculiarities of scientific Latin throughout its historical development.

My attention was struck, for instance, by the subtle ways in which scientific Latin adapts and repurposes classical vocabulary to fit new observations and discoveries. Consider the verb refringo (and the editors’ note on p. 197). In antiquity, it normally means “to tear”, “to break open”, or the like, but Pliny the Elder (Natural History 2.150) atypically uses it to refer to the scattering of sunlight through a layer of clouds. Much later, in the seventeenth century, the physicist Francesco Grimaldi coins the new term diffractio from the same Latin root—lexically paving the way for the emergence of the wave theory of light in the process, and with it a wholly new understanding of the phenomenon.

Similarly, the noun conductor (p. 100) can mean “hirer”, “tenant”, “contractor” and several other things in classical Latin, but certainly not “electrical conductor” in the modern sense: the situation is very different in the eighteenth century, when Luigi Galvani uses the term profusely in his pioneering writings on the relationship between electricity and muscular innervation (now known as ‘galvanism’).

In sum, one of the main accomplishments of The Latin of Science is to show that the history of the language used by scientists goes hand in hand with the history of science itself.

Needless to say, there is more work yet to be done. Are there stylistic hallmarks of scientific communication in Latin across the ages? What about the ‘geometric subjunctive’ dear to the Euclidean tradition (Sit triangulus abg… “Let abg be a triangle…”), or the didactic ‘question-and-answer’ prose of Kepler? And for that matter, do Arabo-Latin translations display linguistic features not found in scientific texts originally written in Latin? These and analogous questions are outside the remit of this excellent academic book, but can perhaps indicate avenues for further research.

In conclusion, Epstein and Spivak’s The Latin of Science is an outstanding achievement by any yardstick. The volume undoubtedly deserves a place in the library of any scholar interested in the history of science from antiquity to the modern age or in the persistence of Latin in European knowledge traditions after antiquity. It also, above all, offers a ready-to-use pedagogical resource—particularly well-suited for introducing STEM students to Latin.

If Classics is to survive and thrive as a field of study in the twenty-first century, it must not only grapple with the ever growing pressure on students to major in scientific and technological subjects, but actively engage in fruitful interdisciplinary conversations with them. The Latin of Science is a very welcome step in that direction, with hopefully many more to come.

Marco Romani is Outreach Manager for the Paideia Institute. He takes a particular interest in the history of science, and the role Latin has played in that history.

Sign up to receive email updates about new articles

Comment

Sign in with