Roman Fountains — An Appreciation

From One Lover of the Eternal City to Another

I’ve always found it a little sad that so many teachers, when asked what they do for their students, claim that they are making critical thinkers. Critical thinking has its place, of course, but unless you want to drown in your own negativity, it’s always going to be a small place compared with something like appreciative thinking, or right action. I take more pride in the fact that I found an Aronia arbutifolia growing in the wild for the first time yesterday, and planted a blueberry bush, than in all the perfectly apt critical comments I directed at the world during the day. I don’t think I’m wrong in this estimation, and whenever I think about teaching, I know my goal is to share with students a little bit of the love I feel for this world. To me that’s the thing that’s really enduringly worth sharing.

And I’ve looked for the same as a student: I’ve always been attracted to the teachers who are motivated by love and willing to share it with me. And I look for it in books too. And when I find love in them, I’m enchanted.

Recently I found such a book, and I wish to share it with you as well. I had never heard of this book until an ad popped up for it on a website I was visiting. It was called Roman Fountains. I knew of the wonderful tone poem by Ottorino Respighi, the Fountains of Rome, but I had never heard of a book on the topic. The ad wanted me to know it was for sale on eBay for $50. (Now that I make a lot of internet purchases due to quarantine, my ads are getting more and more ad hominem).

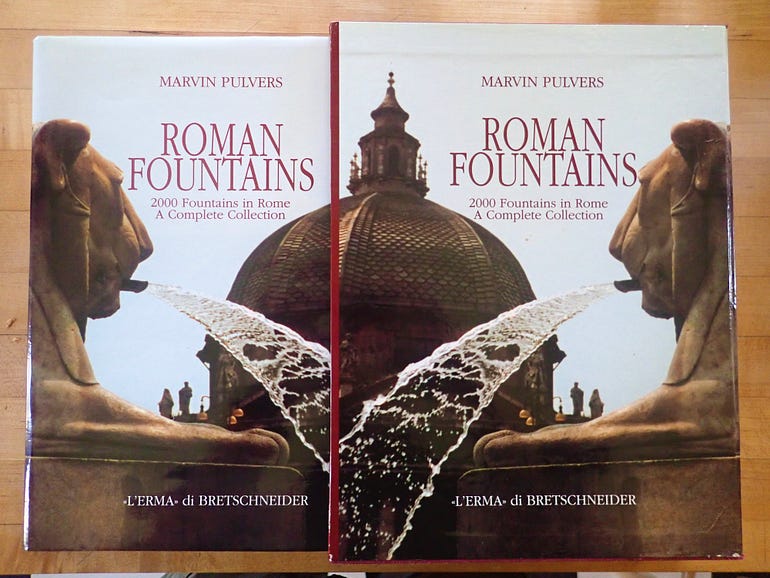

The book cover sported a pretty picture of an Egyptian lion spewing a jet of water from its mouth in front of the church of Santa Maria dei Miracoli in the Piazza del Popolo. This is the kind of thing that gets me to click. The book’s subtitle was “2000 Fountains in Rome: A Complete Collection.” Wow — someone went to the trouble of learning about and writing about 2,000 Roman fountains? To do ten would be a remarkable achievement. Two thousand? I was impressed. The book was a big coffee-table book. The copy was signed by the author. It was fifty bucks — expensive for a book, no doubt — but my birthday was coming in a few days and I’m at an age where I can’t really expect other people to get me gifts. And it came in one of those pretty slip covers. Not only that, some were selling for $900 on Amazon. I could claim it was an investment. But more than anything else, it was a labor of love — books like this don’t get finished without love — and love always makes me want to draw nearer.

When I got the book, I lingered a bit over the inside front cover, where the author inscribed the book to his friends Lee and Sid, thanking them “for all of your friendship over the past 40 years and the sharing of so many happy events and occasions.” It was dated 2002. I thought about it; the friendship started 58 years ago. The author, Marvin Pulvers, and his friends Lee and Sid were old. More than that, Lee and Sid were probably dead: they died, their things were dispersed and sold, and ended up on eBay. I don’t know this, but it’s as good as guess as any. Inscriptions in books like this always make me pensive: this very object was handled by those people now gone; the object is here and they are not. It never ceases to be a mystery, no matter how often I think about it.

I think they must be dead in part because this is not the kind of book you give away, once you’ve got it. It is beautiful, more than 900 pages of photographs, the first 115 pages of them color. It’s heavy too: the eBay seller must have spent half the money I spent on it for shipping. I sat down to enjoy it.

It was everything I could have hoped for. The preface reads like it was written with real Roman aqueduct-water for ink. It also reminded me of so many expat days in Rome: Pulvers tells the tale of how the book came to be. He hired a taxi for a day to help him take pictures of a few fountains; he liked the taxi driver, Aldo Novelli, who boasted that he knew every fountain in the whole city (a boast Pulvers believes). They had fun; they did it again. Pulvers dreamed of photographing them all and doing a book, but then the mad infinity of Rome got involved:

In truth, if in the early stages I had know that there were as many fountains as I finally located, it is extremely unlikely that I would ever have contemplated undertaking this project…. After I had photographed the first 100 fountains, I purchased a book on the subject, which described about 200 fountains. I made it my goal to photograph those that I had not already shot. I naively assumed that it listed all of Rome’s fountains. How foolish! A second book was later recommended to me. And it was with mixed emotions that I saw that it contained more than 400 fountains, noting that some of the 200 in the first book didn’t appear in the second…. With nearly 1,000 fountains on film, I became committed to the idea of publishing an account of “all of Rome’s fountains.” As the year 2000 approached, the number of fountains I found and photographed also approached 2,000. The connection was apparent. I deeply desired to document 2,000 fountains in time for the end of the year 2000.

It was a labor, of course — I shudder to think of trying to keep the documentation straight on 2,000 anythings — but he didn’t lose the love:

I might add that each day’s effort was a new adventure. I never tired of “discovering” a new fountain, nor did I ever tire of the challenge of taking its photograph. Frequently the portiere or the guard was reluctant to allow me entry to the building or its courtyard to see and photograph the fountains. Scores of times I was told “non si puo” (it is not possible).

In one instance, I had to return five times before gaining entry. Then, it was only after going through four levels of employees until the director was available and finally said “va bene” (okay). In another instance, I returned several times and went through numerous layers of command without success, until the original guard, fed up with my regular visits, asked me how long it would take to shoot the picture. When I told him that it would be less than a minute, he said he would turn away from the fountain for one minute and then I could take the picture and leave. And the guard was quite happy to see me go.

In another instance, when the portiere offered the usual “non si puo,” I asked how much it would cost to buy the building. Believing I was serious, and that I might do so and not require his services, he said, “Okay, take the picture.”

“Government buildings and banks,” he says with glorious understatement, “were a particular challenge.” All this was done in the good old days of letters too: “My work included sending hundreds of letters requesting permission to photograph the fountains of villas and palaces. Ringing doorbells was more common than not to gain entry. It never became a chore…. Somehow, if all were there just for the taking, the pleasure might have been diminished.”

There is something of the expat in Rome in all of this. Pulvers might be a figure in a movie or novel about Rome; he is only squinting through the keyholes of great Rome, but he gets a sense of the greatness of the place all the same. I’ve had conversations with people like him, people who had some angle on Rome and wanted to give themselves to it. Sketching all of the old belltowers. Finding all the 14th century frescos. Visiting all the mosaics commissioned by Paschal I (or is it Paschal II?). Photographing all the hands represented on the Capitol, from Marcus Aurelius to the Spinario to the Capitoline Hand itself. We’d toss out ideas like this over those unending meals, and some people even got well started on their projects. But Pulvers actually had the madness to keep going.

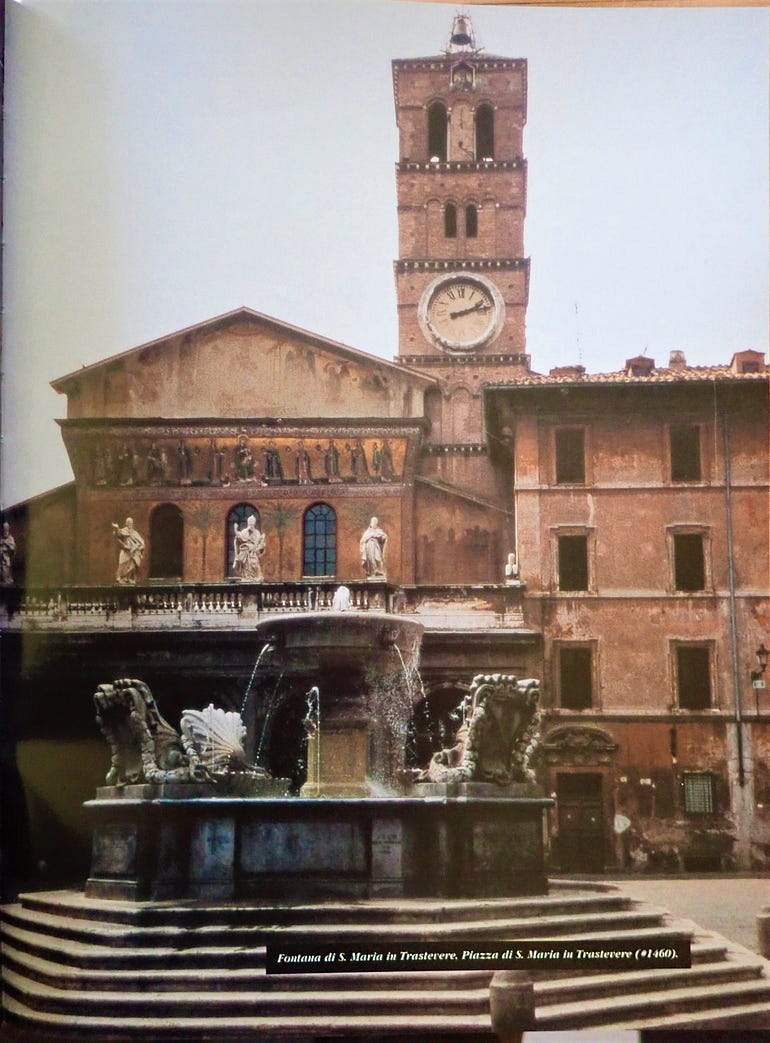

The result, for those of us who love Rome, is just wonderful. It’s especially wonderful for those of us who knew the city in the 1990s, when most of the photographs were taken. The picture of the palazzo next to Santa Cecilia in Trastevere just about melted my heart, those old sangue di bue walls, the stains and filth of the whole 20th century written in red plaster, that was the Rome I knew. E.U. money came and restored all those buildings so they now look as fresh and new as the Italian palazzos you can buy in Beverly Hills.

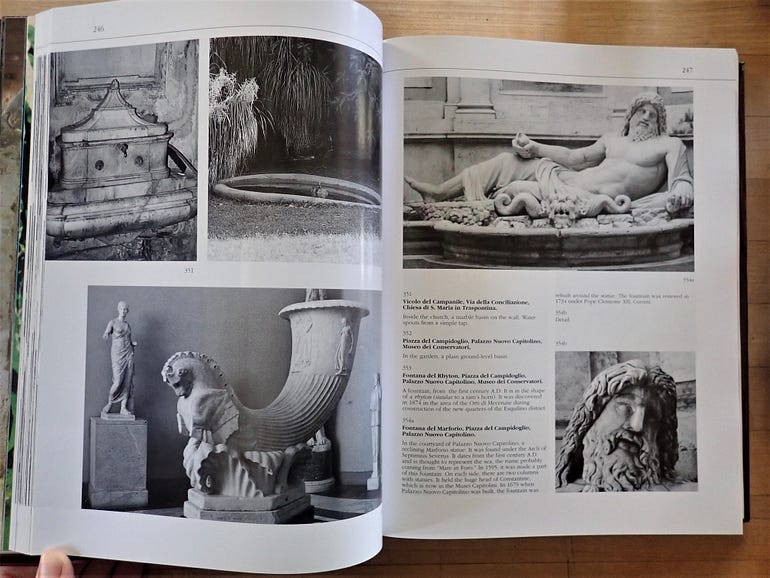

And besides all the pictures, there’s the mad Faustian exhaustiveness of it all, which is enchanting: “Dozens of books, many of them titled Le Fontane di Roma, have been written on this subject, none to date has covered in text and photographs together more than several hundred fountains.” He even photographs some nasoni (though not all), I think just as a joke. The book is organized by street, so if you have a favorite Roman street you can walk down it from fountain to fountain with Pulvers’ pictures — the Via Giulia, the Via del Corso, the Via Appia. And since no book about Rome would really be complete without one, Pulvers includes a quotation from Shelley (ludicrous comma included): “The fountains of Rome are in themselves magnificent combinations of art such as alone, it were worth coming to see.”

The book is not cheap (as I said Amazon has some for $900), but when bargain copies come along, grab one, if not for yourself, for your friend. It makes a lovely book for Rome-lovers to daydream over. I wish Marvin Pulvers were still alive so I could treat him to a half of bottle of wine in some Trastevere dive — or interview him for this space — but the internet tells me he passed away in 2013. Marvin, I hope you can see up there how happy your book makes me, and how much I appreciate it.

John Byron Kuhner is editor of In Medias Res.

Sign up to receive email updates about new articles

Comment

Sign in with